Why the Oromia Opposition Parties Never Ever Learn

A famous intelligent person once said, “Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results.” That is precisely the dilemma Ethiopian opposition groups and liberation fronts find themselves in today. Despite repeated betrayals, failed negotiations, and a rigged political landscape, opposition parties continue engaging with a regime that has never once demonstrated a willingness to compromise. This is not a simple case of political miscalculation. Rather, it is a predictable cycle seen in authoritarian regimes worldwide, where opposition forces are drawn into an unwinnable game—a game carefully designed to legitimize the ruling power while offering nothing in return.

Ethiopia’s ruling party, Prosperity Party (PP), is not a government in the traditional sense but a zero-trust regime. Negotiation, for them, is not a mechanism for resolution but a tactical move to stall, confuse, and manipulate. Historically, authoritarian regimes have used such maneuvers to their advantage. In Russia, Vladimir Putin’s government allows opposition figures to participate in elections, not to provide democratic choice but to create the illusion of legitimacy. In Zimbabwe, Robert Mugabe’s ZANU-PF engaged in political negotiations with the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC), but each supposed democratic step only solidified the ruling party’s grip on power. Similarly, in Egypt, the opposition plays a role in a staged democracy where outcomes are predetermined. Ethiopia is no different. The ruling party engages in “talks” not to resolve conflict but to gain time, disrupt opposition forces, and manipulate international perception.

History shows that authoritarian governments do not negotiate in good faith. The Pretoria Agreement, which Ethiopia was compelled to sign under international oversight, has already been violated. Previous negotiations with the Oromo Liberation Army (OLA) in Tanzania turned into a deadly farce, where the regime used the opportunity to attempt round up and eliminate unsuspecting fighters while talks were still in progress. These actions are not accidental missteps; they are deliberate strategies. In a system where power is non-negotiable, the function of negotiations is merely to serve as another battlefield—one of deception rather than bullets.

If elections were a genuine democratic process, then the decline of PP’s support in Oromia would matter. But in a controlled political environment, public sentiment is irrelevant. Ballot counts are predetermined. The ruling party remains in power, whether through direct fraud or an electoral process designed to ensure their victory. This is another common pattern seen in regimes where elections serve as performance rather than process. Ethiopia’s PP is following a well-worn path. Their interest in Oromo opposition parties is not a sign of political openness but an attempt to exploit them for short-term political expediency.

However, the regime’s need for a renewed political spectacle suggests that its image has taken a hit. PP’s repeated claims of having “crushed” the OLA have not materialized. Despite boasting about defeating OLA within two weeks, then one month, then three months—each promise proving empty—the armed resistance continues to gain ground, notably through its campaign under Duula Cichoomina Kaayyoo (DCK). The regime’s media machine staged an elaborate ceremony to declare the surrender of OLA forces, complete with peace doves, Abbaa Gadaa elders, and all the theatrical pomp of a state occasion. In reality, the event was nothing more than the defection of a single commander who had been facing disciplinary action, along with a few low-ranking associates—some of whom were regime-planted operatives pretending to be fighters. Rather than signifying OLA’s defeat, the surrender spectacle was an act of desperation.

The deeper crisis for PP, however, is not just its military failures but the deteriorating economic and political situation. Corruption, once concealed beneath layers of bureaucracy, is now openly exposed by figures like Jawar Mohammed and other independent sources. The state’s brutality and financial mismanagement have eroded whatever legitimacy it once held, reducing it to a shell propped up by propaganda and fear. Yet even in the face of this decay, the upcoming elections will unfold as expected. The regime will win, regardless. The election is not about counting votes but reaffirming the ruling party’s permanence.

With its legitimacy severely bruised, PP now seeks a fresh way to appear credible to the international community. Domestically, no one is fooled. The Ethiopian people understand the charade of democracy in a zero-democracy setting. But internationally, institutions like the IMF and donor nations still require some pretense of political competition to justify engagement. This is where opposition groups become useful. By participating in an election that is already rigged, they provide the regime with a veneer of legitimacy. Even if they are granted token positions in “government”, their real role is not power-sharing but power-ratifying. Their involvement signals to the world that the system is “open” when, in reality, it remains sealed shut.

Opposition groups must recognize that engagement with an unyielding regime will yield nothing. The regime does not need genuine dialogue, nor does it need fair elections—it only needs to maintain the illusion of both. By taking part in this charade, opposition figures are not resisting authoritarian rule but reinforcing it. A fundamental shift is required: away from participation in a rigged system and towards strategies that challenge the system’s legitimacy at its core.

Now, returning to the specifics of the Oromia case:

- The regime’s claim of having crushed OLA is a demonstrable falsehood. Despite setting multiple deadlines for OLA’s destruction, the armed resistance remains intact and has even registered notable victories under the campaign of DCK.

- The so-called “surrender” event orchestrated by the regime was little more than political theater. A single defector, facing internal disciplinary action, was paraded as a major victory. The presence of fake fighters and regime operatives only reinforced the artificial nature of the spectacle.

- The economic crisis, compounded by rampant corruption, has left PP more vulnerable than ever. Figures like Jawar Mohammed have exposed layers of theft and brutality within the system, with more exposés expected, further alienating the population.

- Despite these vulnerabilities, the election outcome is predetermined. The opposition is being courted not for meaningful political reform but for image rehabilitation. The real audience is not the Ethiopian people but international actors like the IMF and donor nations who seek at least the appearance of democracy before continuing financial engagement.

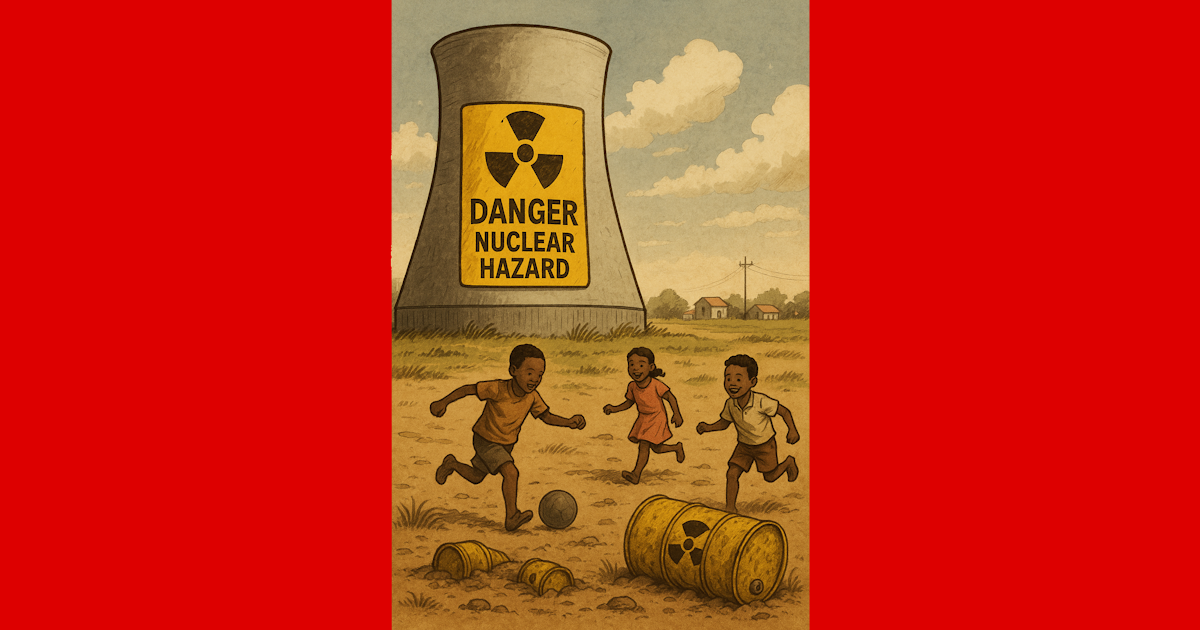

Whatever actions the opposition takes, it must be understood that the regime will always emerge victorious in a system it controls. By engaging in discussions, negotiations, or elections without structural changes, the opposition does not weaken the regime—it strengthens it. In simple language, from opposition standpoint, it is like discussing or negotiating with a brick wall. To recap a historical fact, since the words ‘democracy’ and ‘democratic’ entered Ethiopia’s political vernacular after the imperial era ended in 1974, no political discussion or negotiation in the name of the Oromo people has ever produced a positive outcome.

What the Oromia opposition parties must ask themselves is this: What do they not already know about this zero-trust regime? What lessons do past experiences teach? What trust exists for any meaningful outcome from discussion? It is all the same cycle, repeated endlessly, expecting a different result. By now, we all know what that is.

The only path forward is to reject the role of legitimizing a false democracy and instead pursue alternative strategies that disrupt the system rather than sustain it. Opposition leaders must abandon the illusion that change will come through a game whose rules are set by the regime. Instead, they must embrace resistance strategies that deny the regime the legitimacy it desperately craves. They must stop being props in a fraudulent democracy and start being forces of real disruption.

The question is not whether the regime will change on its own—it won’t. The question is when the opposition will stop playing along. If they won’t, they will bear full responsibility, for they fully understand the immense political deficit their actions inflict upon the Oromo people they claim to represent—a betrayal history will neither forget nor forgive.