When Language Colonizes: The Amharic Illusion of Progress

When Language Colonizes

In the landscape of African colonization, one recurring justification for conquest and domination has been the civilizing mission—carried out not just through force, but through language. From the French mission civilisatrice to the British insistence on “English education,” colonizers offered language as a “gift”—while using it as a tool of control.

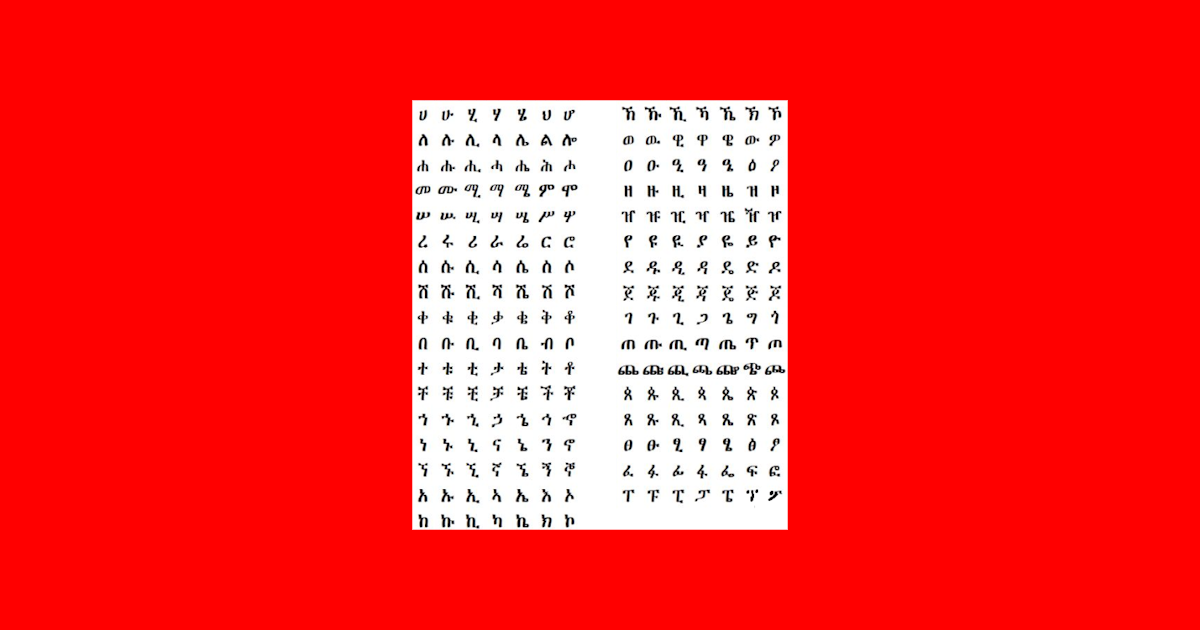

In the Ethiopian case, however, the dynamic is strikingly internal yet equally colonial: Amharic—by virtue of being a written language—was not only elevated as the sole native script in Africa (despite evidence pointing to its foreign origins), but also promoted as the Oromo people’s first gateway to civilization and modernity—a narrative advanced in parallel with European colonialist ideologies.

This claim, still echoed by some Amhara elites, is both historically shaky and ideologically loaded. It is akin to telling an entire people that their indigenous systems of knowledge, governance, and oral tradition held no worth—until validated by the script of their conquerors. In this, Ethiopia’s internal colonization mirrors—and in some ways surpasses—the cultural assault that came with European colonialism elsewhere in Africa.

Let us be clear: the presence of a written script is not synonymous with civilization. While writing facilitates the preservation of knowledge, it is not the sole vessel of wisdom or social advancement. The Oromo, with their Gadaa system—a sophisticated and democratic institution of governance—have long demonstrated an indigenous model of social order, checks and balances, and peaceful power transfer. It is a system that predates modern constitutions and speaks to a cultural depth that requires no external validation.

The Amharic Illusion of Progress

The supposed gift of Amharic came not wrapped in partnership, but in forced assimilation. It was part of a broader political strategy aimed at erasing the identity of annexed peoples and forging a monolithic empire. Unlike the post-colonial African states where colonizers—despite the brutality—eventually retreated and often left behind infrastructure and a recognized national identity, the Abyssinian project sought to absorb, assimilate, and rebrand its annexed internal “others.”

For Oromos, Amharic was not just a language; it functioned as a mechanism of dispossession.

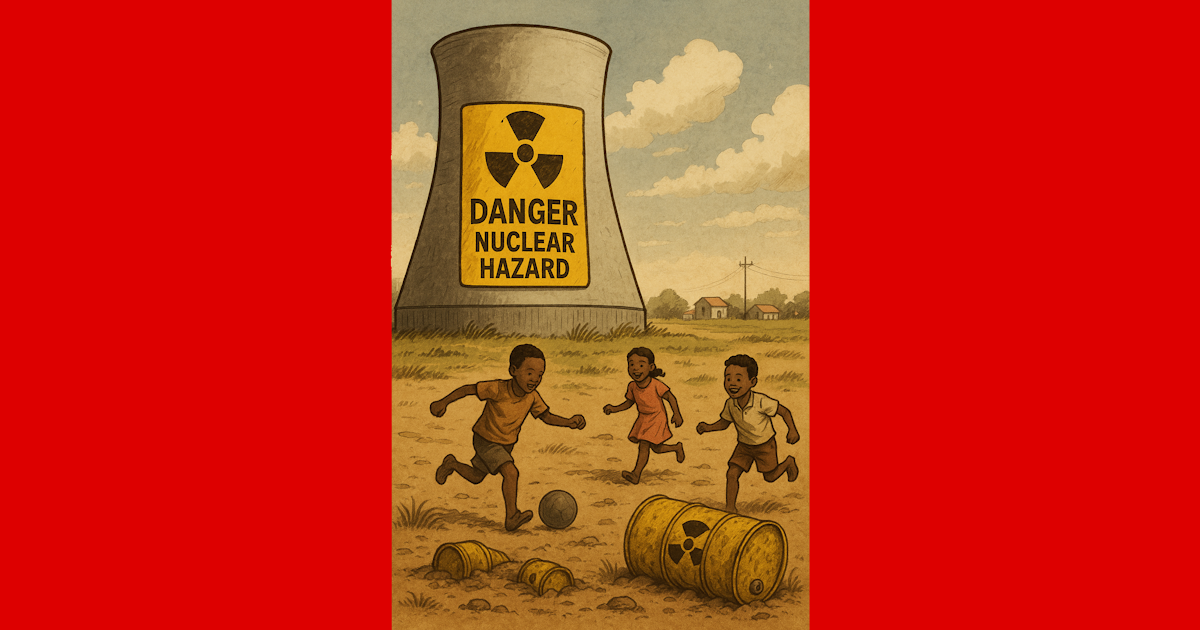

One of the most glaring injustices was that Amharic—alongside core subjects like Mathematics—was made a compulsory subject for advancing to higher education. This policy remained in place until it was abolished by the military Derg regime. As a result, many Oromo students were systematically denied access to higher education, not because of academic inability, but because of a language barrier deliberately woven into the educational system. To this day, there are Oromo elders who recall being excluded from the opportunity of higher education simply for not mastering a language that was never theirs to begin with.

The systemic discrimination embedded in the use of Amharic extended far beyond education. It permeated the entire social fabric—acting as a barrier not only to employment and career advancement, but also to accessing essential public services. Fluency in Amharic became a gatekeeper to dignity, opportunity, and recognition. Those who lacked fluency were often perceived as less capable, less cultured—and, disturbingly, less human—in the eyes of the system. For many Oromos, their native language became a mark of exclusion, while Amharic stood as a linguistic wall between them and full participation in national life.

When the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) helped usher in the post-Derg political transition in 1991, one of its pivotal acts was adopting Qubee—the Latin-based script for Afan Oromo. This wasn’t a political stunt, but a linguistically grounded decision. Amharic’s script, as has been demonstrated in scholarly analysis, is fundamentally ill-suited to capture the phonology of Afan Oromo. Using it would have meant distorting the language, much like colonial systems often imposed foreign scripts on local languages to ease administrative assimilation.

Yet, more than 30 years later, some Amhara elites still express grievance that Oromos abandoned Amharic. Their discontent is not linguistic—it is political. The Oromo’s decision to reclaim their language, their script, and their narrative is a challenge to a hegemonic vision of Ethiopia. It is a rejection of the myth that one nation must disappear for another to shine.

No one denies that Amharic has literary value or historical relevance. But to claim that it alone carried the torch of civilization within Ethiopia is a form of cultural gaslighting. It dismisses the lived experience, oral traditions, and indigenous wisdom of over half the empire’s population. And in doing so, it repeats the logic of every colonial empire that insisted it was bringing light to the “darkness.”

To claim that Oromos should be grateful for Amharic, as some Amhara elites brag, is as tone-deaf as telling Kenyans they should thank the British for English while glossing over the Mau Mau massacres. Worse, in Ethiopia’s case, the colonizer and the colonized still live within one state—and the campaign to delegitimize Qubee and Oromo linguistic autonomy continues even now.

The truth is stark: Oromos were never in the dark to begin with—and certainly not for lacking Amharic.

Like other African peoples, they would have engaged with global languages—English, French, Arabic, or even their native language Afan Oromo—as needed. But they would have done so on their own terms, not as subjects of forced assimilation, but as agents of their own knowledge systems and destiny.

There is sporadic historical evidence suggesting that Latin-based writing systems for Afan Oromo emerged as early as the period when Oromos were first exposed to Amharic. However, these early initiatives remained undeveloped, largely due to the threat of persecution for using Oromo script in place of Amharic. Isolated experiments appeared independently in pockets of both eastern and western Oromia. Had the Oromo people been left to chart their own linguistic path—unhindered by annexation and forced assimilation—there is every reason to believe that today’s well-developed Qubee script could have taken root much earlier.

Conclusion

To move forward, Ethiopia must recognize that no language, no culture, and no identity holds a monopoly on civilization. The true gateway to progress is mutual respect, historical honesty, and the dismantling of internal hierarchies masked as cultural pride.

Should Oromos be grateful for Amharic, as some Amhara elites insist? Not at all.

The language arrived not as a neutral medium of communication, but as a calculated vehicle of forced assimilation and cultural erasure—compounded by its intrinsic unsuitability for representing the phonological richness of Afan Oromo.

To equate the presence of written Amharic with Oromo progress is as flawed as claiming the Oromo people would have remained in darkness without it. That logic is as absurd as claiming the sun ceases to exist at night—an illusion born of blinkered vision, not reality.