H Huriso (Author)

Foreword by OROMIA TODAY

Ten Minutes‘ Mission is a true account of life as Oromo political prisoner by H Huriso during the the Dargue regime spanning the time from 1970’s to early 1990’s. The manuscript is intended to make it into a printed book and in its current form comprises some twenty-five chapters. Obbo H Huriso has kindly given permission to Oromia Today to serialize the chapters under the Feature heading and we are ever so grateful for this generous offer to our online readers.

Dedication of the Manuscript by the Author

In memory of my comrades: Muhe Abdo, Kebede Demissie, Yiggazu Waqee and Gezahegne Kasahun, who remained in the backyard of the headquarters of the Maekalawi*, and to my dear mother.

H Huriso, 2016

* Maekelawi (literally central) is a cental police station in Addis Ababa where jail cells are used to incarcerate political prisoners and infamous for its extreme torture techniques and executions. Jail cells are used as prison cells indefinitely. It was a common practice to pack in political prisoners like sardines, particularly during the peak times from late 70’s to mid 80’s, to the extent that one only gets enough space to stand up. Don’t even imagine a more humane cell for one or two persons we’re used to on TV screen. [Ed. by OT]

Prologue

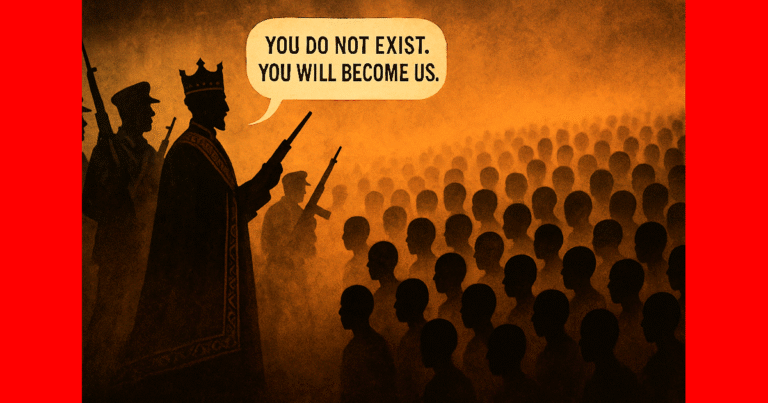

November 1977 to May 1978 was the time of brutal violence in Finfinnee, aka Addis Ababa. This period is commonly known as the era of the Qey Shibbir [literally, red terror] , the terror that was incited by the conflict between rival factions: the military junta in power, aka Derge, and the opposition groups over the leadership of the leaderless revolution of the oppressed peoples. It was marked by mass executions of the ‘enemies of the revolution’. The death toll was in tens of thousands.

This period was when the social fabric in the country was dismantled and the very human life was reduced to somewhat meaningless. In these days, kidnapping or killing squads led by the military junta roamed around day and night, and hunted down or pulled out young educated, or rich and prominent individuals out of their houses, even from their beds or from their work places, or simply grabbed just from the streets and gathered them in temporary storehouses as makeshift prisons, from where they took every evening and executed summarily. Each of the 292 kebele (local district) in the capital city had such storehouses. It was when even the cellars in the palace compound, including the palace wine storehouse were changed into makeshift prisons.

If you were there in those days, you could have listened in the evenings to roaring machine-guns throughout the city and the next day, you would see corpses of young, mostly innocent people, who had been pulled out from the storehouses and machine-gunned the previous evening. You could have seen also these corpses of the ‘enemies of the revolution’ lying like rubbish in all dead enemy exhibition centers such as the main streets or squares and even in front of the very doors of the victims own houses to provoke the parents. They let their corpses lay there the whole day with placards bearing the slogans ‘We intensify the Red Terror, or Red Terror will flourish…’ written in the blood of the victims and pinned on the chests or backs of the corpses. It’s all intended to rule and control with fear and terror but it was an unimaginable brutality unfolding in front of our eyes. If you looked around, you could have seen mothers or relatives shedding their tears in silence and looking from a distance if the corpses of their sons, daughters or relatives – who had been taken away days or nights before and never came home – might had been in that ‘human dump’. Or had you been in the Menelik hospital, you could have seen parents or relatives taking the corpses of their beloved ones for a fee five Eth Birr (about 50 cents). The fee is for the price of the bullet that did the killing. Imagine the insult on the top of savage brutality.

This was the tragic legacy of the February revolution of 1974: the revolution of the broad masses of the oppressed peoples, the revolution without a visible leadership and a visible organization, but a revolution with a visible vision, a vision to regain their robbed birth rights and justice. Being kidnapped and machine-gunned became part of the normal daily life. Every day, people going out were never sure of their coming back home. Many left their homes in the morning but never returned. If they were lucky to be alive in some unknown prison, they did make home after many years. As a result, tens of thousands of the educated section of the society on which the families and the nation invested for a quarter of a century perished for nothing. Many innocent parents lost their lives in defense of their children. Many home lives were disintegrated in no time: many children became orphans and lots of women were widowed. I heard lots of horrifying news and witnessed many shocking incidents in those months. The Almighty saved me three times from falling into the mouth of those hungry Red Terror hyenas that were opened for others. I had to wait for my own turn though.

On January 28, 1980 I went to my office for a short moment. It was Monday afternoon, two years after the flames of the Red Terror dwindled down to flickers and everything seemed to calm down, but that Monday I never returned home, not until nearly twelve years later.

The story in this book [serialized here by a chapter] is a result of a long time hard work, through professional therapy, to let out much of the bitter experiences behind the iron bars as an Oromo political prisoner.

Chapter 1

A Messy Monday Afternoon

It is about half past two. I lie on my bed and wonder with my eyes in every corner of my small room aimlessly. A part of me that faced a scalpel some days before hurts; I had a minor operation in my groin. In a few hours, my sick-leave days will come to an end. The unsafe atmosphere at the work place deprived my internal integrity. Everything is really unsettling. In spite of the mental burden, I tried to stand up. I must go to the office, because I had an appointment with someone that afternoon. I could not change the appointment because he comes from far away – nor I miss meeting him. It was a matter of life and death. I must go also against the wish of my sister. She begged me not to go out because I was just recuperating.

I rose to my feet and paced in the small room: forward and backward. I could go. I wore my shoes, put on my Lialf coat I bought a week before and left the room. I closed and locked the door, and walked for some steps but I thought I had forgotten something. I turned back, reopened the door and went in but I couldn’t recall what I thought I had forgotten. I closed the door again and went to the main road some fifty meters away. I stopped there for a while without any purpose and looked at the busy human and vehicle traffic on the small bending narrow road in front of me. Four shoe-shiners rushed and kneeled at my feet. I shook my head in negation. I turned left and walked across a bridge on the formerly called Qamalee River and walked toward the Berhanena Selam Printing Press. It was a matter of minutes. It was hot, typical of a January weather in Finfinnee: hot days and cold nights. At noon, the sun heat stings from above and the heated asphalt scalds from below. At night, it is cold and frosty in the morning.

It was exactly three o’clock when I arrived at the main gate of the Printing Press. Workers who were coming back after lunch-break and those arriving for the afternoon shift had crowded the narrow gateway.

Dramas at the checkpoint

There were two organisations in this compound: the B.S. printing press and the Press Department of the Ministry of Information. This necessitated long queues for entrance check-up which became a usual practice ever since the beginning of the Red Terror when people were pulled out of their work places or offices and killed. I remember one incident every time that took place at this gate, at that time. One day, some persons, a pregnant woman among them, were taken out from this compound and machine-gunned by a notorious cadre labelling them as the members of the EPRP, the group that splinted from the former. On that very afternoon and hour, my friend B. D. and I had escaped from the same misfortune for a matter of minutes just in front of the Ministry of education building, some fifty meters away. We ran back to the University compound. In the Street fighting, that afternoon and evening, between the MEISON and the Derg on the one hand and the EPRP on the other, thousands of youngsters, including some of my friends, were mowed down by machine-guns.

Since that day, to go into government buildings or nationalized organizations, entrance check-up became a norm. Security men were stationed at the entrance and checked anybody that comes in no matter how many times they went in or out, no matter how she or he was familiar in the compound or at the gate and no matter how high his or her position was. The only exceptions were the ‘guads’ or comrades – ‘the true sons of the Revolution’. They went in and out at will with their pistols dangling from their waists. There were two queues: one coming from the east and the other from the west – both along the main road on to which the gate opened. Both queues merge into one at the very gate where the searchers: a man and a woman checked those coming in if they were armed or not. I joined the western queue and dragged myself forward.

This was my second time, in three days, to come to this compound since I took a sick-leave some days before. In between, I received a message that I had to report to the office of the manager of the Press Department. It was a hectic time and I became curious to know why. A week before, my boss called me to his office and showed me a letter in which he was ordered to be a member of the military party, Abiyotawi Seded . I was embarrassed and told him that he shouldn’t show me that letter. He asked me if I was also a member. I told him that I would not tell anybody if I were a member. I expected the same question from the press department head. I went on the Saturday before to his office on the seventh floor. It was in the late afternoon when I arrived. There was a dead silence. I stood outside for a while and mulled things over in my head what I should say if he would ask me that question. Without any answer in my head, I knocked at the door – with hesitation. There was no answer from inside. I knocked again and opened at the same time and said good afternoon! The secretary – a very huge, polite and sociable woman – greeted me friendly and showed me respectfully the comfortable sofa in front of her. I sat down. She put the folder and a ball-point in her hands aside and opened her drawer as she was talking to me about the weather, took out an envelope, came forward and gave it to me. I received and opened it just in front of her, took out a one page letter with two short paragraphs and read it – I reread it again. It was an appointment letter signed by the Minister.

They promoted me to the position of an acting editor-in-chief of Bariisa, a weekly Oromo language newspaper, where I took a refuge two years before. I had been working for this newspaper for the last two and a half years – first as a reporter, then as a page editor, on a national democratic revolution and at this very latest moment as a vice editor-in-chief. This letter terrorised me as the letter demanding the membership of Saded from the editors. I didn’t show her any reaction. I thanked her, I folded the letter, put it in the envelope again and looked at the woman. She was looking at me silently, the whole time I think. ‘Congratulation!’, she broke the silence. She said from the bottom of her heart – I felt so. I thanked her. ‘You are very fast. It is good but sometimes not. There are lots of problems up the ladder of responsibility. The more you run up very fast without enough experiences the more will be the problems. Anyhow, I wish you a happy end and more success; take care!’ she said. All what she said was meaningless for me at the time. I thanked her and left the room. Before I put the letter in my pocket, all the problems related to Bariisa I had experienced in the last six months came and stood before me like a mirage.

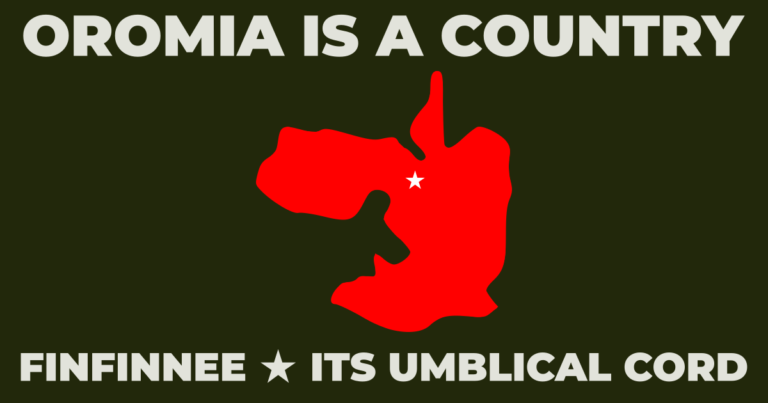

The Bariisaa Newspaper, then, was only five years old. It was initiated, first by an Oromo, Mahdi, in 1975 on the revolution day as a two pages leaflet. Other Oromo who were inspired by the sweeping changes in the empire joined him and developed it into a weekly Oromo language Newspaper – the first newspaper ever in the Oromo language. The initiator named this Newspaper Bariisa. It was not without a reason, I believe. Literally, the word Bariisaa means dawn, the daybreak, the appearance of the beam of light. The founder of this Newspaper, however, meant the appearance of the beam of freedom and the end of a century of darkness for the Oromo and other peoples in the south who suffered in the ‘Qigniland under a especial rule called: Gabbar Sire’at and ‘Neftagna Sire’at’, and experienced unprecedented hidden political oppression, archaic economic exploitation, cultural enslavement and unheard of hidden human degradation.

After its establishment, Bariisa became very popular among the few literate Oromos despite the difficult Sabian alphabet used to print it. In a short period of time, it became as popular as the weekly Amharic newspaper, the Zareyitu Ethiopia. The sons of the Neftagna who hijacked the popular revolution found this very offensive. To halt this development, they took it over under the cover ‘to appreciate the move’ and added it to the newspapers run by the government and put it under the control of the ministry of information where it became, mostly, a direct translation of the government newspapers and its circulation was reduced to a mere 4,000 copies, and later to 2,000. The problems of Bariisaa did not end there. The meagre issues that come out every week were blocked from reaching the readers and its consumers were reduced to mere staff members of the paper. The government news agency sends most of the copies to non-Oromo regions: to Eritrea and Amhara country, like Gonder. Over 150 copies were sent to the Derg office where nobody even wants to see it let alone to read it. Underground hooligans were organized to harass the boys who sell this paper by beating or robbing the paper and burning en-masse in some areas. The copies remained in the store were sold in bands to the shop keepers for wrapping articles. The Bariisaa staff made numerous complains but there were no ears to listen. They raised the problem once in front of the Minister of Information on one of the study circle (a compulsory weekly political indoctrination meeting to be attended at workplace). This was summed up with a short comment ‘The problem of Bariisaa is the problem of our revolution’. Through the editor-in-chief, anti-Bariisaa movement tried time and gain in different ways to let us agree that something of the newspaper be changed in which a column would be in Oromo and its translation in Amharic in the next column. The editor-in-chief, let them talk with me twice. It was impossible really to know whether these people were hooligans or the security men. I didn’t know them nor did I see anyone of them with my own eyes. We talked over telephone. At first, I tried to convince them that Bariisaa was a direct copy of Addis Zemen in Oromo Language in most cases. We played this game for some time.

Finally, they started the process from the above. The bureaucracy itself formed a committee of three men including the editor-in-chief, all non-Oromo, to tour all the Oromo regions and gather a consensus that may lead to the closure of the Newspaper. The three men committee went to some towns like Ambo, Jimma, Laqamtee, Asella and Dirre Dawa for three weeks and supposedly talked to the kebele [district] leaders. To their surprise, they came back with a long list in which individuals, urban dwellers and even peasant associations subscribed to Bariisaa. In the Arsii region, the peasant associations wanted over a thousand copies and Oromos in the cities of Dirree Dhawa and Ambo asked for 700 and 500 copies, respectively. This plan was stopped.

The editor-in-chief and the other committee members disappeared for unknown reason. There was a telephone call from all places asking for their newspaper according to the agreement. I had collected these messages and reported to the responsible officials. There were no ears. It was at this last critical hour that they gave me this post. I had been reviewing all complications related to it ever since I had received the letter two days before. With this conflicting problem churning in my head, I reached a checkpoint. Two security persons in plain clothes: a man and a woman were searching the pockets and bags of the incomers. Other security men stood around with their Russian Klanshkoves dangling from their shoulders.

At the junction of the two queues, there was a massive blood of a young man who was shot dead, with the unsightly blood left undisturbed, drying and caking on the asphalt road for others to see as a reminder of what could happen to them. The unfortunate young man, a proof-reader at the printing press, was accused of having a ‘counter-revolutionary leaflet’ in his possession and was sentenced to death on the spot by execution at this very gate. That was the only crime for his execution. It was neither a legal court, nor a military tribunal that gave the verdict; it was carried out by local leaders of a [political] study circle, in effect, taking the law into their hands (and of course with the tacit approval of government officials). They were the security men, the police and the judges at the same time.

The victim was an Oromo by birth. He was a high school dropout and earned about twelve dollars per month to live on and support his poor mother. He might have dreamt like others that the revolution had come for him to make his life better but an abrupt and criminally insane end to his life. The so-called revolution didn’t come for him, it came to him, to take him away. The ‘revolutionaries’ had a sinister slogan to justify the elimination of those undesirable members of the oppressed with extra-judicial executions: ‘A revolution eats its children’. According to the eyewitnesses the others before him were also machine-gunned in the same place.

This was a shock for everybody, witnessing a fellow human being slaughtering his own kind; and nothing comes to mind to compare such brutality and madness with. What was even more shocking was the brutal and criminal acts being perpetrated by the very people in high offices who promised better life and freedom to the oppressed masses. Everyone who passes that checkpoint must tread on the blood of those tagged ‘anti-revolutionaries’ with an unimaginable shock. I had a share of the shock too, as there is no option to avoid the route.

At about one hundred meters behind the checkpoint, there was a second the check. This time the guards of the printing press do all over once more. When I arrived, there was no queue. I stretched my arms and stood in front of a humorous old guard. I found his apt jokes on the prevailing conditions a kind of distraction one needs. Every face that frowns at the check-point never went past him without a broad grin. He ran with his hands on both sides of my arms, then under my armpits down to the shoes and looked at me: ‘You have a tank in your secret pocket. Don’t you?’ he said. ‘No, I have Mig 23,’ I said and made my way to the lift.

‘Stop, militia police,’ one announced behind me as if to command the lift to say open. I entered the list just in front of him and tried to press the button for the sixth floor which was already pressed and the door bang shut. I tried to inspect the four walls of the lift as you’d normally find political slogans affixed there but I couldn’t see any on this occasion; the lift was full to the brim. I looked around. Everybody was looking down and there was a dead silence. I did the same thing. The lift dropped people at every floor and got to the sixth floor I was the only one. It was a dead silence here. There wasn’t any moving body.

I went directly to Bariisaa office. One of my colleagues, Kuwee, was in the room. She told me that some people were looking for me; she couldn’t tell me who they were. I thought the person I was expecting that afternoon may be came with someone else. I went out and looked around; no one was there. I took the lift and went down to the compound. I couldn’t see any kind of new faces.

***

I went to the new office of my departing boss and told him about the letter I had received from the press department, and expressed my worry about what was going on in Bariisa. I couldn’t detect any good feeling on his face. After a little silence, he told me calmly that he had given his personal recommendation that I was a “true democrat” as far as he knew me and that I was the right person for the position. He told me also that he hadn’t any time. That was very surprising. I left his room without any comment.

Plenty of thoughts invaded me, significant of all, the problems of Bariisaa and about this mysterious man; I wanted to go back to the Bariisaa office and wait for my guest. This time, I was alone in the lift and I was uplifted to the six floor in no time, while skimming through the slogans on the lift walls without any obstruction. These are some of the most colourful slogans that stick to mind: ‘Forward, with the Revolutionary leader!’ ‘We will establish the Workers Party!’ ‘The theory of merging parties is the slogan of the Trotskyites!’ ‘We’ll intensify the Red Terror!’ ‘Those who vacillate will die with two bullets!’ ‘Everything to the war fronts!’ ‘Our revolution knocks at every door!’ ‘A revolution eats its children!’ All of these were relatively old, with some of them scratched and others with big red crosses over them.

As I came out of the lift, there was a dead silence as before. On the way to the office, I wanted to say, ‘Hello!’ to a friend of mine in the Al-Alam weekly Arabic language paper office sharing the same floor. He was a reporter there. They print this newspaper purely for propaganda but sell to shops for wrapping articles, because nobody read it except the editors and perhaps the Arab diplomatic circles who may be keen to monitor the governments propaganda campaign with printed media.

I called ‘Mohammed!’ and at the same time knocked at his door; he was not in. I passed and went directly to Bariisa office at the end corner of the corridor behind a glass door, opposite to the lift on the west side of the L-shaped building. I opened the door and went into the small square hallway. On the left was the office of the editor-in-chief, which I was supposedly going to occupy the next days. In front of this on the right was the office of the office secretary.

Just in front of me was a big room shared among the junior reporters and proof-readers. My office was between the office of the editor-in chief and the room of the proof-readers. As I came into the hallway, I heard a roaring laughter from inside my room. ‘What is that?’ I shrugged. I moved back to the entryway and stood for a moment and then tiptoed to the door. I stuck my head into the doorway and tried to listen. I felt as if someone was coming out. I ran back but nobody came out. I returned and tried to listen to the voices again. It was the same.

This office was bigger than the office of the editor-in chief. We shared it for three. Two senior reporters, Kuwee, a very active, sharp minded young lady and Bullo, a young man sitting to my right in an open plan office. They often argued almost about anything and laughed but the voice I heard was more than two and I thought perhaps there were other reporters and proof readers. We often had reporters come to our office when major incidents took place such as arrests, house searches or killings.

By now being in the state of so many thoughts in my head, I finally decided to go into the office, as if to surprise them, by opening the door slightly and popping in my head. As it happened, it was more of a surprise for me-the room was full of new faces. I took a quick look around. My eyes fell directly on a man sitting on my chair. I thought I had gone to a wrong office but it was the right office. Holding the handle of the door, I glanced blindly around with a lightning speed. Kuwee was sitting in her place and flipping some papers. I could detect the sad expression on her face and lack of the usual sparkle. Bullo was not there.

I knew only one of the four men there. He was a reporter of Addis Zemen newspaper and the leader of a press department wiyiyiit kibeb [1]. ‘Come in, Mr.…. we have been waiting for you,’ said the man sitting on my chair, rocking from side to side. He continued talking as he stood up and came out from behind the table.

‘We need your help. We have asked permission from the manager of press department and he agreed that you would go with us somewhere for a mission. ‘You will come back in ten minutes,’ he said.

Before he finished his sentence, the other two men fell on me. Everything was clear. They were the members of jibo[2], the Derg security squad, who hunt and arrest or kill undesirable people and those labeled as anti-revolutionaries. I used to hear about this sinister jibo name and shocking stories of their cruelty. That day and that minute, I saw face to face those devils that killed and maimed thousands of innocent lives and disintegrated as many families.

I held my breath and blinked my eyes. With my mind between a dream and a reality, I stood there while they were chaining my hands and digging into my pockets, and rummaging in and around my drawers. The two men grabbed my right and left arms and hustled me out of the room. They shoved me through the narrow corridor to the lift. One of them pressed the button and the door was opened. They hurled me in. The door was closed and the lift made its way down.

‘Read this?’ said the man I had seen sitting on my chair, pointing his finger to one of the slogans pasted on the wall of the lift. It reads: ‘We intensify the Red Terror!’ A soaked person never fears of rains says an Oromo maxim. ‘Red or White,’ I said as if mockingly. He did not react. The lift came to the ground floor. The door was opened and we went out. There was a huge human traffic outside. I stole a glance here and there. Nobody raised his head and looked at us. The two men were still hanging to my chained hands.

We left the compound. There were four cars outside. Two of them were full of armed men in plain clothes. They were parked on both sides of the check point. Two men were busy with on a walky-talky. The men hanging to my hands shoved me into an empty Opel car and three men with Kalashnikovs got in behind me. There was a dead silence and we stayed like that for some time. I thought there were more to be arrested; otherwise, they didn’t need that much man power or stay so long.

***

Finally, the man who told me about the mission got in and sat in front of me in the passenger seat and the arrest vans started moving one after the other but not to the direction I had expected. The car with a walky-talky moved first and then one of the cars with the armed men. The car carrying me was the third to move. They rolled toward the so-called tamama gambi[3], the ministry of education under which I once worked in the past as a teacher, and so called by teachers nationwide for its poor administration. The convoy then turned right and continued eastward. I was just wondering where they were taking me when the car carrying me turned left, crossed the main road and stopped at the gate of the so-called Grand Palace. This at the time was the headquarters of the ruling military junta. The huge, old gate was opened wide and the car carrying me moved in and stopped at about one hundred metres in the back yard. I was ordered to get out. One of the armed men showed me with his left hand the direction to which I should move; left hand was the sign of a revolutionary. I moved to that direction and the three guards followed me. In a couple of minutes, we were at the door of an old, low and detached building in the western flank of the palace compound. One of the men pushed the door open and let me into a long corridor stretching on both sides of the door.

Namaat, a more significant woman in the case I was to be accused of later and whose husband disappeared some days previously, was sitting in the left side flank of the corridor. Our eyes met and she smiled sourly. Everything became clear for me. The men led me to the right side of the corridor and ushered me into a big room. It looked like a courtroom. There was a big, long table, and many chairs behind it and a chair on the front side. I sat on this front chair, closed my eyes and began to listen to the voice of Angasu, an energetic and enthusiastic young man, talking to me in a restaurant on one of his last days in the city. ‘I see you sitting behind iron bars and shaking your head.’ He predicted correctly, I did it but I never regretted.

Few minutes later, the guards came back and let me out. Namaat was no more there. They took me back to the car. The car left the palace compound and rolled back to the direction from where they took me. It circled the square before the ‘crocked building’ and turned toward the B.S. Printing Press. I thought they were going to kill me at the checkpoint like the others before me because I didn’t have a clear idea about the process of the Red Terror. The car passed the checkpoint, rolled to the direction of my house. It stopped exactly at the entrance to the compound where I lived. I was sure that they were going to search my house.

The squad leader and the driver got out and walked toward my house and then halted at a small square where they used to gun-down young people in the evening during the Red Terror. The two men came back, very fast, got in and the car rolled toward Piazza district in the city. It turned right at the General de Gaulle Square and stopped. The two men got out once more and walked for some distance across the road, stood and talked for some minutes and then came back. The car raced up then to the St. George church and then further up to the notorious Third Police Station (aka Maekalawi) where I had been expecting to be taken when they took me out of my office but it stopped in front of iron gate of former Italian buildings (of World War II era) few meters before the police station.

The gate was opened and the car rolled in and stopped. The guards opened the doors and got out. One of them ordered me, quite rudely, to get out. It was totally uncalled for. I replied, rather unconsciously, with the same tone as if to show my rage, which I never experienced in my life before. One of his colleges gave me a nasty bang on my back seat using the butt of his gun. I turned back to him with anger. Their leader barged between us and pushed me aside. I staggered and collided with a passer-by who hurled me back. I lost my footing and stumbled onto the pavement under the feet of another passer-by who helped me to stand up.

The jibo took me into the back compound to a kind of narrow corridor with a low ceiling and stopped in front of one of the closed doors. The squad leader knocked at the door, opened it and looked inside. Then, he took hold of the chain on my hands and pulled me towards him, slapped me once on both temples with the force he could muster, threw me in and slammed the door closed. It felt sparks of different colours flickered in front of me. I couldn’t see anything around me for a few minutes. I rubbed my eyes and tried to look around. Four men stood in front me and another was sitting behind a table. All looked at me in silence. I looked around. The room was small. I couldn’t guess for a second what it was and who the people were. The four men left the room wishing a goodbye to the man behind the table.

Then the man stood up and greeted me, and showed me a bench in front of him. I sat down. He looked at me for a while and then called a name. A short man came from the back room. He told him something I didn’t pay attention to. The man turned back to his room and came back with a big registry book. He registered my name, my father’s and mother’s names, including my grandparents’ on both sides of my parents; my birthplace, age, education, profession and current work and place of residence, a very exhaustive process that too several minutes. Then, he told me to put all my belongings on the table. I put there my belt, watch, handkerchief, shoes, socks, ball point pens, money and my wallet. He gathered them and went back.

After registration, the man behind the table who was looking at me the whole time said: ‘We are sorry that you are here; I wish your case will be cleared soon and you re-join your family. Until then, you stay here with us. You will get your things back when you go home. Here, there is no food and no clothing and no mattresses. If you have a family, who can bring what you need, we can pass your message to them, if you want,’ he said. I didn’t say anything. Just at this time, the door flung open and a young, tall man in his twenties came in with both hands in his trousers’ pockets. He bowed down and looked in my eyes. ‘Why did they shackle you?’ he said with an irritating expression. The man behind the table looked at me as if he was expecting an answer for the question. I didn’t say a word. ‘Anti-socialism, anti-people, anti- revolution, anti-peace’ – he spitted all new terms he learned in the wiyiyit kibeb. ‘We have enough imperialist bitches in Eritrea. We don’t need more,’ he shouted with his eyes bulging out.

‘Enough! He is now in custody of the law,’ said the man, as if what they’re doing is lawful. ‘Let him; he is sick,’ I said. This made him angry and he uttered all abusive words with quavering voice. The man shouted at him. He left the room. Next, the man behind the table and another one brought me to another room where my fingerprints, photos were taken and they measured my height and weight and we went back to the small room. The man called someone’s name again and a man came. ‘Go with him! He shows you where you stay. Do you have a family? You need clothes and food’ he said with friendly voice. I shook my head, followed with ‘No!’

The man took me out and led me through a gate of a corrugated iron sheet into another small backyard compound. On the way, he asked me lots of questions. I didn’t answer any. Then, we came to a corner where four old men in different uniforms: Territorial Army, former bodyguard of the Emperor, the army and the police force stood. The man handed me over to these men and went back. An old man registered my name in a big book on a small table. Two others took the chain off my hands. A tall heavy iron gate in front of me creaked noisily to open. A short, fat man stood inside. One of the guards gave him a sign and the man invited me in with the gesture of his head movement.

I stepped in and the gate was closed behind me. The man led me along a long narrow open corridor. I followed him glancing right and left. On both sides of the corridor were many open rooms staffed with people, some sitting, some standing and looking at me. We came to the end of the corridor where the man stopped in front of a door. ‘Again!’ I muttered in a shock. My arrest had never shocked me like this. I closed my eyes in despair. The man talked to a young man standing at the door and a huge middle-aged man came to the door. They exchanged some words I never heard because I was in another world.

The man invited me in. I tried to step in. The cell was tightly packed and the I could feel the warm air gushing out on my face. Absent-minded, I stood on the threshold. There was no alternative. All eyes in the cell fell on me; it was embarrassing. A young man sitting at my feet left his place for me and pushed his way further back. I crouched down in his place. Immediately I sat down, a young man came and whispered into my ear. Rule number one: a new comer must take a shower before joining this family. He brought down a plastic bag hanging from the wall, took out a bar of soap and a towel and handed over to me. Another man took me out. We turned left and walked some three steeps and we were in front of the door of a relatively wide empty room at the very end of the corridor.

Someone stands at the entrance with a pair of scissors in his hand. He showed me a clumsy chair in the corner. I knew this ceremony already, at least in theory. One doesn’t enter a prison cell with hair. I sat on the chair and he removed my hair in a matter of few minutes. The man told me to collect my hair on the floor. I gathered and threw into a nearby rubbish bin.

The other man led me next into an open room. I took a short shower and came out. There was no other moving life in the corridor except a third person following us the whole time. We returned to the cell. I got this time a better place because I was baptized to join the new community, the new community the so-called revolution is creating. I looked around hastily. Every eye in the cell was on me. It was too heavy to bear. I ignored them and ran with my eyes over the four walls and ceiling. I was in this cell for about twenty-one hours when I was taken prisoner on one of the mass-arrest days in February seven years earlier. I looked at the corner where I stood most of the time. There wasn’t any visible change. I glanced here and there to see if there were stains of blood like it was at that time. There wasn’t a trace of any kind.

A number of mattresses were rolled and laid along the walls and used as seats. The others were piled here and there. I sat on one of the piled mattresses beside a sick man who lied near the wall. There were two other sick men on another piled mattress. It was very quiet and everybody was busy. Some play Chinese checker, others chess, dominoes and cards. The rest were either watching the games or chatting in pairs very slowly. A young, sociable man brought me a very small loaf of bread and a cup of water expressing his regret that I had arrived after they had their supper. I didn’t have any appetite at all; I drank the water. Some minutes later the person standing at the door clapped his hands and made an announcement. He said something I didn’t understand. Everybody left the cell at once, except the three sick men and four other men.

The men, except the sick ones, came back and sat in front of me on the floor, and appeared as eager as little children gathering to listen to story telling. I wondered what would come next. There was a complete silence till the young who offered me a loaf of bread broke the silence. ‘Today we have a new comer. As usual, we talk to him,’ he said. He explained to me also what they were going to do with me as part of the culture of the house as the cell was called. ‘We introduce us to him and he introduces himself to us,’ he said, looking at his friends and at me one after the other. Then, he introduced himself and the others followed him. I did the same. ‘We are sorry that you are here. We wish you that you go home very soon. As long as you stay here, you have to know something related to the daily life in this compound in general and in our cell in particular,’ he said.

Next, he tried to give me the picture of where we were. He told me that there were two blocks known as the lai bet [4] and the tach bet [5]. The term had no special connotation other than a mere geographical indication. He told me that they assigned me to the upper house and continued his explanation. ‘There are over 960 prisoners in both blocks in this evening. In our cell (sixteen square meters) alone, there are forty-two prisons tonight. You are lucky to have a space – six brothers are transferred to Karchale[6] today,’ he said. He explained to me how they lived: how they get food and about the rules and regulation of the cells and the compounds. Before he finished his explanation, those who went to the toilet came back. He told me that they would continue later. They dispersed.

Few minutes later, again the person, who stood the whole time at the door, clapped hands and said something I didn’t understand. The three sick persons and all the rest got up. I was told to join them. The man who followed me when I took the shower whispered to my ear: ‘Don’t talk to anybody. It is forbidden’ he said; his eyes were always on me. All of us went to the toilet and lined up. Priority to use the toilet was given to the three sick men. In a very short time everybody cleaned themselves.

[1] a political indoctrination study circle where the military junta uses to closely monitor who is who

[2] one who behaves like a hyena

[3] crocked building, an ironic expression referring to its poor administration for nation schools

[4] upper house

[5] lower house

[6] a distortion of an Italian term carcere – meaning a jail.