The background to this story is told in a BBC report.

A group of Ethiopian slaves were freed by a British warship in 1888 off the coast of Yemen, as they were being taken to the slave markets of Arabia. The freed slaves were then taken round the African coast and placed in the care of missionaries in South Africa.

All the 204 slaves freed by Commander Gissing were from the Oromo ethnic group and most were children.

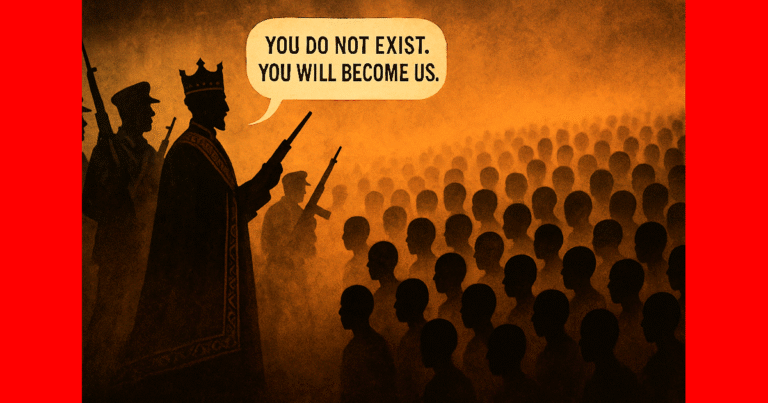

The Oromo, despite being the most populous of all Ethiopian groups, had long been dominated by the country’s Amhara and Tigrayan elites and were regularly used as slaves.

Emperor Menelik II, who has been described as Ethiopia’s “greatest slave entrepreneur”, taxed the trade to pay for guns and ammunition as he battled for control of the whole country, which he ruled from 1889 to 1913.

Commander Gissing took the Oromo to Aden, where the British authorities had to decide what to do with the former slaves. The Muslim children were adopted by local families. The remaining children were placed in the care of a mission of the Free Church of Scotland – but the harsh climate took its toll and by the end of the year 11 had died.

The missionaries sought an alternative home for them, eventually settling on another of the Church’s missions, the Lovedale Institution in South Africa’s Eastern Cape – on the other side of the continent.

The children reached Lovedale on 21 August 1890.

The missionaries recorded detailed histories of the former slaves, educated them and baptised them into the Christian faith. They were given the choice of returning to Ethiopia or remaining in South Africa. Most chose South Africa and when the Anglo-Boer war broke out in 1899 six of the boys joined the British side.

The story of their role in the war is by Dr Sandy Shell, author of “Children of Hope: The Odyssey of the Oromo Slaves from Ethiopia to South Africa”

“Six of the Galla lads educated at Lovedale are now known to be serving with the British Forces in South Africa. They are

- Milko Guyo (with Sir George White’s Force at Ladysmith)

- Gamaches Garba (with Sir George White’s Force at Ladysmith)

- Tolassa Wayessa (with General Buller’s Force)

- Amaye Tiksa (with the Force in the neighbourhood of Naauwpoort)

- Hora Bulcha (with the Force in the neighbourhood of Naauwpoort)

- Wayessa Gudru (with the Force in the neighbourhood of Naauwpoort).”

From the “Lovedale News” Christian Express (1 March 1900)

Tolassa Wayessa

Tolassa’s schooling was over once he earned his Teachers’ Elementary Certificate and he left Lovedale in 1898. By May 1899, he was employed in East London as an assistant to “Mr Scott, photographer,” and then as a waiter in a restaurant in the same city.[1]

In October 1899, the Anglo-Boer War (or South African War) erupted and rapidly engulfed the entire country.[2] Within months, Tolassa enlisted to serve in the British army and by 1900 he was a transport driver[3] with the forces under General Sir Redvers Buller[4] in Natal.[5] Whilst serving under Buller, Tolassa wrote to Lovedale recording his wartime experiences and these letters are reproduced in full below:

“Acton Homes, Natal, Jan. 22, 1900

We left Maritzburg on New Year’s Day and came to Estcourt. Left Estcourt after staying a week. From Estcourt we came to Frere Camp, after a day and night’s march. We did not remain long at Frere Camp; we came on to Springfield. In all these marchings, man after man dropped out on the way. Some were worn out by the long marching and others through want of water. At Springfield Farm four spies were caught—one English, and two Dutch and one Native. They were sent to Maritzburg.

After two days stay at Springfield we left the place. All tents were left there. We started at six a.m. and marched a whole night. In the early morning we were within a few miles of Tugela River, and our guns began shelling. Firing went on till about 11 a.m. At about 12 two bridges were made across the Tugela one for the waggons and other for the troops. In crossing the river one man was killed belonging to the Dorsetshire Regiment; two wounded belonging to the Devonshire Regiment. These men were building the bridges when the Boers shot at them one Boer was caught afterwards. The same day while crossing the Tugela one of the 13th Hussars was drowned and the transport mules belonging to the Dublin Fusiliers. It is going on for four days since we came here and on three of those days we have heard nothing but the sounding of cannon and the hissing of bullets overhead.

Yesterday and the day before yesterday 12 cannon were in action. To-day there are more of them in action. It is said that 322 men are killed and wounded today. Of course, we do not know exactly how many are killed on the side of the Boers. It is said that their trenches are full of dead. In every engagement the Boers are being driven back farther and farther. Before yesterday they shelled the position where we were and killed one man, wounded about half-a-dozen others and killed a number of transport horses and mules.

It is easy to speak about war, but it is very hard to look on dead and wounded men. I did not like to look at the man who was shot by the shell of the Boers. The shell knocked through his breast and came out at the back. We have two naval guns and one Maxim in every regiment and howitzer batteries. The Boers are almost surrounded on every side. They are on three hills, on the right, left and front.

Figure 11: Buller in Natal: the war arena with direction of Acton Homes arrowed

Source: UCT Digital Collections: BMX 684.b.1 [110]

They are driven from the left hill to the centre and right hills. General Buller was here yesterday and today. Our transport is in the fighting line, while the transport belonging to other regiments keeps about half a mile from the regiments. Being under cover of the guns a number of our mules were shot. I cannot tell you all that is going on just now, but I will tell you some time, if I return safely.”[6]

Later, in July 1900, Lovedale received two further letters from Tolassa. The first letter was written at Glencoe, relating his harrowing experiences after leaving Acton Homes:

“The two terrible battles were that of Spion Kop, when we had to retire during a dark and rainy night across the Tugela, and that of Colenso at the relief of Ladysmith. At Hussar Hill and Colenso I was very nearly blown to pieces by shells. The one at Hussar Hill was a 40 pound shell, and at Colenso a shell from a 15 pounder long range gun. At the relief of Ladysmith my regiment was the second to enter the town, and I tell you the town was in a very bad condition. The soldiers were just like moving skeletons. How these men, who were scarcely able to handle a rifle or carbine, kept out the Boers is really wonderful. After the relief of Ladysmith I was transferred to the Special Ammunition Column of the Royal Artillery. We were stationed at Ladysmith about one month; at Elandslaagte over a month; and now my column is here at Glencoe. Dundee, Glencoe and Hadding Spruit were taken with scarcely any fighting. We are leaving for Newcastle perhaps to-day or to-morrow.”[7]

Tolassa’s third letter came from their encampment at Newcastle. According to Lovedale, he started this letter with a description of the “smashed up” condition of Newcastle and of the coal mines, and then continued:

“Coming from Glencoe we passed a number of Boer prisoners, who were captured between that and Newcastle. These poor Boers were very downcast. At one place while they were passing a line of thirty outspanned waggons, all the native occupants of the waggons gave them three cheers. At another place a lot of Cape Boys and Kaffirs came round the unfortunate prisoners and began asking for “Pass!” “Pass!” which no doubt must have cut them to the heart. The Boer trenches are found all over from Colenso to Dundee. At Colenso the trenches are very wonderfully constructed. They are of all shapes and sizes. Some are chiselled out of solid rock, and need no roofing as those do that are dug out of the soil.”[8]

Tolassa had experienced more than his fill of the brutalities of war after these months directly in the line of fire. He quit military service and returned to the Eastern Cape. Towards the end of 1901 he wrote to the Lovedale missionaries saying he intended leaving South Africa in January the next year and that he would travel via “Bombay to Broach” (now known as Bharuch) in India before returning to Ethiopia – by which time the Oromo lands incorporated into ‘Abyssinia’ by Menelik II.[9]

[1]“The Gallas” Christian Express (1 May 1899): 67.

[2]11 October 1899 signalled the outbreak of hostilities between the British in the Cape of Good Hope and Natal and the two Boer territories to the north (the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek/South African Republic (Republic of Transvaal) and the Oranje-Vrijstaat/Orange Free State). At root was the threat of dominance, influence and material interests of the British Empire over these non-British possessions in South Africa. The war continued until the signing of the Treaty of Vereeniging on 31 May 1902.

[3]While the war was primarily one waged between Boer and British, it drew members of all population groups into its service. Many black people enlisted to serve in an unarmed, non-combatant capacity most often as transport drivers or labourers. Transport drivers and wagon-leaders earned a monthly salary of 90 shillings, considerably more than the general labourers who earned a mere 40 to 50 shillings per month. André Wessels The Anglo-Boer War 1889-1902: White Man’s War, Black Man’s War, Traumatic War (Bloemfontein: Sun Press, 2011), 116-117.

[4]General Sir Redvers Henry Buller (7 December 1839- 2 June 1908), a British Army officer, served as Commander-in-Chief of British forces in South Africa in the early period of the Anglo-Boer War and subsequently commanded the army in Natal. Despite his award of the Victoria Cross, Buller was reputedly a poor leader and worse military strategist and for every military success his troops achieved they suffered as many failures during the Anglo-Boer War. As the historian Richard Holmes commented, Buller performed progressively worse the higher up the military hierarchy he moved, declining from “admirable captain” to “disastrous general.” He returned to England in November 1900 with his military reputation considerably tarnished.

[5]“The Gallas.” CL MS 17,125: 6.

[6]“Letter from a Galla Boy” Christian Express (1 March 1900): 35.

[7]“Letters from the Natal Front” Christian Express (2 July 1900): 99.

[8]“Letters from the Natal Front,” 99. From 1760 the white authorities in the Cape of Good Hope required slaves to carry passes authorizing their mobility between urban and rural areas at all times with severe penalties for anyone found unable to produce a “pass” on demand. These Cape laws to control the movement of the majority black population were adopted throughout the emergent South Africa and persisted until formally repealed in terms of the Abolition of Influx Control Act in 1986. Michael Savage, “The Imposition of Pass Laws on the African Population in South Africa, 1916-1984” African Affairs 85, 339 (April 1986): 181-205.

[9]“Lovedale News” in Christian Express (1 January 1902): 4. Of the sixty-four Oromo children who had arrived at Lovedale in 1890, fifteen had died by 1902, the year the twenty-five year old Tolassa Wayessa decided to return home to Ethiopia. By 1902, only five other Oromo had been successful in their attempts to return home independently, all of them young men: Amanu Figgo, Galgal Dikko, Gamaches Garba, Nagaro Chali and Nuro Chabse. All five had returned individually during 1901.