By Professor Mohammed Hassen April 25, 2019

Georgia State University

This paper attempts to briefly discuss the development of Oromo Nationalism and the continuous multi-faceted attack on Oromo cultural, civic and political organizations. The paper aims to show that the attack on Oromo political and cultural institutions which began during the imperial era, continued through the period of garrison socialism, and still continues under federal democratic republic of Ethiopia. In short, the paper shows that imperial, socialist, and federal Ethiopia has not produced a government that did not attack Oromo national identity, Oromo political organizations and cultural institutions, and a government that respected Oromo rights as full citizens of Ethiopia. The continuity of the attack and low-level killings of the Oromo has triple purposes. The first is to destroy Oromo nationalism (an openly declared policy of the ruling party) by eliminating or smashing1 Oromo political, intellectual, cultural and business elite, who are accused of nurturing nationalism and serving as the ideological fountainhead for the Oromo struggle for self-determination. The second is part of the first. It is to destroy Oromo national identity by undermining the development of Oromo language and cultural heritage. The third, is to eliminate the limited gains the Oromo have achieved since 1991, by systematically destroying the autonomous status of Oromia, with the goal of restoring the pre-1991 status-quo in Ethiopia.

Finally, the paper shows that today the low-level killings of the Oromo and the attack on Oromo civic and political organizations is at its widest from the Sudanese border in the west to the Ogaden in the east, from Wallo in the north to Northern Kenya in the south. In this vast region, the organizationally disunited, militarily disarmed Oromo face the formidable military might of the TPLF-dominated Ethiopian state.

Before I proceed to the main subject three caveats are in order. First, an attempt at a scholarly treatment of the attack on Oromo identity and nationalism over a long period is bound to be a vast and complex subject and cannot be adequately discussed in a short paper such as this one. Instead of a detailed discussion of the subject, therefore, I will begin by outlining the salient features of the attack up to 1991 and discuss in some detail the period after 1991. Second, before I discuss why Oromo nationalism developed only during the 1960s, I will present the background out of which it grew.

Third, “Historians, in general, are more at home when dealing with events that have been allowed to settle over time.”2 Therefore, as a historian, it is easier for me to discuss the attack on Oromo political and cultural institutions before than since 1991, because the former period belongs to history, while the latter is history-in-the-making. However, as I have noted elsewhere ”[a] discussion on history in progress is, by nature, a risky undertaking.”3 No matter how hard one tries dispassionately to discuss the attack on Oromo political and cultural institutions under the successive Ethiopian governments, one cannot escape being accused of exaggerating what has been happening to the Oromo and of indulging in anti-Ethiopia propaganda. My purpose is to document the attack on Oromo identity and nationalism as a scholar loyal to the cannons and standard practices of my discipline. If this discussion encourages a reader of this paper to express concern and raise her or his voice against the unlawful attack on Oromo political and cultural institutions, its purpose will have been fulfilled.

The attack on Oromo political, cultural institutions and national identity began with the conquest and incorporation of the Oromo into the Ethiopian empire created by Emperor Menelik II (1889-1913). Following their conquest, the Oromo institutions of self-government were destroyed, their leadership liquidated or co-opted, their territory divided, their social cohesion disrupted, their cultural institutions destroyed, their property plundered, their traditional religion interfered with, their population decimated through a combination of factors including brutal warfare and natural calamities which accompanied that warfare.4 After their conquest, the Amhara ruling elite headed by Emperor Menelik regarded the Oromo and other peoples of southern Ethiopia “.as sub-human and their culture and languages as inferior.”5 In one Amharic expression, Oromos were equated to human feces “Gallana sagara eyadar yegamal” (“Galla and human feces stink more every passing day”).6 In another Amharic expression, even Oromo humanity was questioned, “saw naw Galla”? (“Is it human or Galla?”7), thus making them “… something less than fully human” resulting in … “their exclusion from the moral concerns of the conquerors.”8 After the conquest of the Oromo, Emperor Menelik abolished the Oromo Chafee assembly,9 thus eliminating the political significance of the Gada system at one blow.

By 1900 Menelik even banned the famous Oromo pilgrimage to the land of Abba Muuda.10 The latter was the leader of traditional Oromo religion; and every eight years the Oromo from every corner of their country sent their representatives to honor Abba Muuda in Southern Oromia. Through this pilgrimage, the Oromo maintained contact with their spiritual father and with one another. The pilgrimage was the focal point for their unity. By banning the pilgrimage, Menelik prevented the Oromo from meeting with each other and, above all, he destroyed the religious aspect of their unity. Once traditional Oromo religion was weakened, the ground was prepared for the imposition of Amhara religion in Central and Western Oromia and the rapid spread of Islam in Southern and Eastern Oromia.

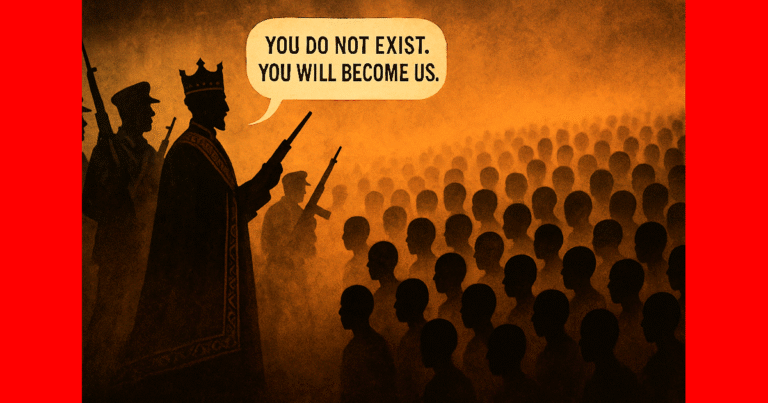

In Central and Western Oromia the Oromo were even denied the spiritual experience of personal conversion to the Ethiopian Orthodox Church Christianity. They were subjected to collective baptism. Once converted into Christianity, Oromo personal names were replaced by Amhara ones. The use of Oromo personal name became a mark of shame and a badge of humiliation. However, “. . . since in the Oromo tradition, personal names locate individuals within kinship structures, such forced name changes led to the alienation of people from kinship ties and caused a rupture in their social history.”11 The goal of imposition of Amhara names, religion, language, culture and way of life on the Oromo was to change them into Amhara society. For that purpose, a policy of Amharization (i.e. assimilating the Oromo into Amhara names, religion, language, culture and a way of life), became an article of faith for successive Ethiopian regimes up to 1991. Amharization was an Ethiopian state policy. It was also an ideology of the Amhara elite. For instance, some of the prominent Ethiopian intellectuals of the early twentieth century were preoccupied with the policy of assimilating the Oromo into the heart and soul of Amhara society. Perhaps what Tedla Haile says about it may sum up the prevailing attitude of the time:

After reducing the protagonists of the Ethiopian polity to the two peoples, Oromo and Amhara, Tedla prescribes the formula for their harmonious relationship. The Ethiopian emperor has three options with regard to the Oromo: enslavement12 and expropriation,13 assimilation,14 and indirect rule . . . . Assimilation . . . remains the only credible and sensible option. As to who is going to assimilate whom, Tedia has no doubts: is for [the Oromo] to become Amhara [not the other way round]; for the latter possess – a written language, a superior religion and superior customs and mores.15

For Sahle Tsadolu, the Minister of Education, the policy of assimilation even involved the banning of the majority of Ethiopian languages. Such a drastic measure was necessary for the unity of Ethiopia, a euphemism for perpetuating Amhara religious, political, cultural and economic domination of Ethiopia.

The strength of a country lies in its unity, and unity is born of [common] language, customs, and religion. Thus to safeguard the ancient sovereignty of Ethiopia and to reinforce its unity, our language and our religion should be proclaimed over the whole of Ethiopia, otherwise unity will never be attained … Amharic16 and Geez17 should be decreed official languages for secular as well as religious affairs and all pagan languages should be banned.18

Indeed after 1941 Oromo language was banned and as a result, it was not permissible to teach, preach, write and broadcast in that language up to the early 1970s. What is more, the government of Emperor Haile Selassie (1916-1974) prohibited the use of Oromo literature for educational or religious purpose and existing Oromo literature, was collected and destroyed.19Oromo cultural and religious shrines and places of worship were replaced by the Amhara ones. Even Oromo village and town names were replaced by Amhara ones. For example Finfinnee became Addis Ababa, Ambo was changed to Hagere Hiwot, Haro Maya to Alem Maya, Hadema to Nazreth, Walliso to Ghion, The Village of Ejersa Goro where Haile Selassie was born, was renamed Bethlehem.20

The goal of replacing Oromo village and town names by Amhara ones, to borrow a great scholar’s apt phrase, was to obliterate, “Every reminder of the former national character”21 of the Oromo. A concentrated and coordinated attempt was made to obliterate Oromo national identity. For that purpose, Ethiopian educational system, cultural institutions and governmental bureaucracy were deployed for the express purpose of denigrating the Oromo people, their history, culture and way of life while ensuring the establishment of the hegemony of the Amhara culture masked as “‘Ethiopian’ culture.”22 In the Ethiopian educational system, nothing positive was taught about Oromo heritage. On the contrary, an Oromo child was “… made to feel his or her mother tongue was inferior and too ‘uncultivated’ to be used in a civilized environment such as school.23

In the school, the Oromo child was not only mobbed; but was ‘fed’ negative biases against everything that was Oromo. Mixed in with the Amharic language and Abyssinian history, he/she was taught many of the Amhara prejudices against the Oromo. The Oromo people were depicted as subjects and dependent in relation to the Empire and its rulers whereas the Amhara and Tigreans were presented as citizens. The Oromo were (are) described as a people without culture, history and heroes. … The Oromo were characterized not only as uncivilized, but uncivilizable. The Oromo language and culture were reduced to marks of illiteracy, shame and backwardness as the school pressed Oromo children to conform to Amhara culture. … Those who were completely overwhelmed by the unmitigated assault on Oromo culture and history, dropped (or tried to drop) their Oromo identity. Among these, were some who tried to get rid of every sign of what the Oromo themselves call Oromumumaa (“Oromoness”). In a desperate move to assimilate they ‘forgot’ the Oromo language.24

With the intensification of the policy of Amharization and de-Oromoization, the Oromo were subjected to total domination in every aspect of life – economic, political, social, cultural and religious. In a very fertile land, they were doomed to live in abject poverty, as their labor and produce supported the large and parasitic Ethiopian ruling class. The contrast between the Amhara landlords and Oromo gabbars (serfs) was striking. There were power, glory, pride, wealth, strong feelings of superiority, pomp, arrogance and luxury on the side of Amhara landlords, while powerlessness, landlessness, rightlessness, and poverty were the lot of Oromo gabbars. who were physically victimized, socially and culturally humiliated and devalued as human beings.25 The Amhara landlords:

. . . Maintained a social and often spatial distance from the gabbar populations that they considered uncivilized and worthy only of exploitation. Before the revolution of 1974, a gabbar was not often allowed to enter the house of the landlord when he brought grain or other products to him. The landlord differentiated little between the gabbar and the pack animal he used to bring him the goods.26

Ernest Gellner, a noted scholar aptly described Ethiopia as “a prison-house of nations if ever there was one.”27 In that prison-house of nations the Oromo language was banned from being used for preaching, broadcasting, teaching and production of literature up to 1974. “In court or before an official an Oromo had to speak Amharic or use an interpreter. Even a case between-speaking magistrate, had to be heard in Amharic.”28 This amounted to an ethnocide which stripped Oromo children of their language, culture and identity and destroyed their pride in their cultural heritage and kept them chained with no faith in themselves, their history, and their national identity,29 “It remains the belief of the Amhara ruling class and elites that to be an Ethiopian one has to cease to be an Oromo. The two things were/are seen as incompatible.30

Oromo nationalism developed as a response to continuous attack on Oromo national identity and cultural heritage. It developed as a peaceful self-help organization with the goal of up-lifting the Oromo spirit, improving their economic condition, and spreading literacy, building roads, clinics and schools, churches and mosques.

Oromo nationalism is still developing and changing. It took shape against several decades of economic exploitation, military subjugation “political and cultural domination”31

Oromo nationalism differs from other nationalisms insofar as the experience of Ethiopian rule differs from that of being ruled by a Western colonial power. Ethiopian colonial power was centered in the country itself and not in some distant metropole. The rulers were also ‘natives’, and did not have immense technological superiority over the ruled nor enjoyed vastly superior standard of living.32

The development of nationalism is a long, complex and slow process. It is mediated by national awakening or national consciousness, which “refers to an amalgam of feelings, impressions and ways of thinking, which find their expression in the psychological and physical solidarity of the group experiencing them in common.”33 National consciousness emerges primarily as a result of several factors including the spread of modern education, better communication, improved transportation system, growth of mass media and the press, higher standard of literacy and growth of literature, and intensive interaction among people, all of which combine to provide “a crucial environment for the spread of a national consciousness through a given population.”34 The overwhelming majority of the Oromo were peasants who lived in rural areas and therefore were not exposed to the factors just mentioned. Even the tiny Oromo elements that lived in urban areas did not have access to education and literature in their own language. It is not surprising then for Oromo nationalism to develop much slower than other nationalism in colonial Africa.

Before the 1960s, the Oromo lacked an intellectual class that aspired to create cultural and political space for itself. Intellectuals are, “predestined to propagate the ‘national idea’,” just as those who wield power in the polity provoke the idea of the state.”35 The lack of an intellectual class not only delayed the development of Oromo political consciousness, but it is still one of the major weaknesses of the Oromo national movement. In the rise of nationalism in Asia, Africa and other parts of colonial territories, the educated class played a very decisive role.36 “It is hard to find a single one of the African nationalist leaders, whether radical or conservative, who was not a graduate of a western university or else had some other prolonged exposure to western life.”37 In the Oromo case, there was no western educated class that aspired to create cultural space for itself before the 1960s, much less to lead a nationalist movement.

In sum, the absence of modern education, the tight control of Ethiopian administration, the absence of an intellectual class, and Amharization policy of Haile Selassie’s government, all delayed the development of Oromo nationalism before the 1960s. Furthermore, from its birth in the 1960s, Oromo nationalism faced strong opposition from the Somali ruling elite. While the Amhara ruling elite feared development of Oromo nationalism as a threat to their empire, the Somali ruing elite regarded it as a dangerous movement that would abort the realization of the dream of a greater Somali.38

Evidently, Oromo nationalism of the 1960s was not a mass movement. Like the early phases of nationalism in different parts of the world, Oromo nationalism of the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s was an elite movement.39 This was because “Nationalism is usually a minority movement pursued against the indifference of members of the ‘nation’ in whose name the nationalist act.”40 Nevertheless, Oromo nationalists of the 1960s knew that nationalism is “above and beyond all else, about politics, and that politics is about power. Power, in the modern world, is primarily about control of the state.”41 The nationalist leaders of the Macha and Tulama Association knew about this reality. And it was precisely for this reason that General Taddesse Birru, a leading figure of the Macha and Tulama Association attempted to capture state power in November 1967 though the attempt ended miserably.

The founders of the Macha and Tulama Association articulated Oromo cultural rather than political nationalism and their officially-stated goal was the search for and recognition of Oromo identity within the larger Ethiopian identity itself. Consequently, they did not reject Ethiopian identity, the state and its institutions while the Oromo nationalists of the 1970s and after, who articulated Oromo political nationalism, did reject Ethiopian identity and its institutions.42

In 1967, by imprisoning its leaders and dissolving the Association, the government of Emperor Haile Selassie won a short-term victory. However, within seven short years, by 1974, its policy unwittingly transformed Oromo politics beyond recognition. The Association’s demand for equality within Ethiopia was transformed into the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) commitment to self-determination for Oromia. Since 1974, according to Ibsaa Guutama, the liberation of Oromia has been on the mind of every Oromo nationalist.43 That marked a quantum leap from the Macha and Tulama Association leaders’ vision for the future of the Oromo. The Association’s efforts to spread literacy in the Amharic language and Ethiopic script were transformed into literacy in the Oromo language using the Latin alphabet. What was unthinkable in 1967 became feasible by 1974. The Ethiopian government’s unwarranted cruelty and brutality- produced the Oromo elite’s rejection of Ethiopian identity itself. For those who rejected Ethiopian identity, the Ethiopian state neither embodies a consensus of beliefs, values and aspirations nor instills in them trust in its institutions, laws, leadership and administrative machinery. On the contrary, these are the tools of oppression and subjugation that have to be removed and replaced. As a consequence, after 1974 Oromo politics was never the same again. What the Ethiopian government wanted in 1967 by destroying the Association was the destruction of Oromo political consciousness. What it got in 1974 was a mature form of Oromo political nationalism which was opposed to Ethiopian identity and directly challenged Ethiopian nationalism itself.44

The Ethiopian Military Regime’s Attempt to Contain Oromo Nationalism, 1974-1991

The 1974 revolution offered Ethiopia an opportunity not only to democratize itself, heal the old wounds, redress old injustice, right old wrongs, but also to decentralize power in the country. “Most Oromos had assumed that the revolution of 1974 would lead to decolonization and equality of all peoples in Ethiopia.”45 The formation of the OLF and the 1974 Ethiopian revolution stirred Oromo aspirations to regain their political rights, human dignity and equality. The revolution not only aroused Oromo pride in their national identity, language and culture, but also raised their expectation to regain their land. After 1974 revolution, land reform of some kind was a foregone conclusion.” Without it, it would have been impossible to take impetus out of the flood of spontaneous Oromo peasant uprisings, especially in Hararghe.”46According to Rene Lefort, it was the fear of Oromo uprising and the desire to prevent it from happening that forced the military regime to take radical measures including land reform.47Asafa Jalata also convincingly argues that the military regime took some radical measures not only to address Oromo grievances but also to get their support and consolidate it.48 Thus, the Derg’s nationalization of all rural lands in March 1975 was a legal recognition of fait accompli, especially in Oromia, designed to arrest the tempo of peasant uprisings. According to Christopher Clapham, instead of devolving power to the peasantry, the land reform of 1975 centralized the power of the state in Ethiopia.49

In April 1976, the Derg declared the National Democratic Revolution Program (NDRP). This program, which became the blueprint for the transformation of “Ethiopian socialism” into “scientific socialism ” was “… the first official policy that recognized Ethiopia’s national diversity.”50 The NDRP stated:

The right to self-determination of all nationalities will be recognized and fully respected. No nationality will dominate another one since the history, culture, language and religion of each nationality, will have equal recognition in accordance with the spirit of socialism.51

However, the NDRP was never implemented and it remained on paper, an empty gesture. In fact, the Derg used the NDRP not only as a showpiece of its radicalism to impress the Soviet Union, but also for waging war against what it called “narrow nationalism”, a euphemism for Oromo nationalism. Narrow nationalism was proclaimed as the main enemy of the unity of the country and the Derg began a policy of physically destroying the best elements of the Oromo society, especially the intelligentsia.

For seventeen years the peoples of Ethiopia suffered under a brutal military dictatorship, whose historic mission was nothing but destruction. It is believed that hundreds of thousands52of peasants lost their lives between 1974 and 1991, not to mention millions of Oromo who were internally displaced and thousands who were scattered as refugees to many parts of the world. When the authors of sorrow and destruction were overthrown in May 1991, there was a sigh of relief, a time of joy and a moment of hope for the peoples of Ethiopia in general and the Oromo in particular. They were to be disappointed soon.

The TPLF Dominated Ethiopian Regime and the Attack on Oromo Organizations

For seventeen years the OLF struggled against the Ethiopian military regime and made a significant contribution to the combined effort which defeated the regime in May 1991. In recognition of this fact, the OLF was invited to participate in both the London Conference in May and the Addis Ababa Conference of July 1991. In the latter thirty-one parties, including five Oromo organizations participated to discuss the future of Ethiopia and draft program of transition towards a democratic order. The OLF co-authored the Transitional Charter with the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Forces (EPRDF), the coalition of the various ethnic organizations affiliated with the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) and then joined the Transitional Government of Ethiopia (1991-1992). The Transitional Government was billed as a coalition government representing three main interests: the Oromo interest, the Amhara interest, and the Tigrean interest, with others … being considered important but secondary.53

For the first time in modern Ethiopian history, the principle of respect for human rights was popularized in Ethiopia and enshrined in the Transitional Charter of July 1991. The Charter was meant to democratize the unitary Ethiopian state which was dominated by one ethnic group and replace it with a federal system in which all citizens enjoy equal rights. By effecting such a profound transformation, it was hoped that the Ethiopian state will be reconstituted into a legitimate sovereign authority that will serve as the accepted “arena … the decision-making center of government,” and the institution that maintains law and order and enhances societal cohesion.54 The future was uncertain, but the prevailing mood among the Oromo was one of optimism. The Transitional Charter had”… laid down major human and political rights principles and55 the transitional period was meant to launch a process of democratization and empowerment of the people. For several months after the establishment of the Transitional Government, there was marked improvement in the human rights situation in Ethiopia.56

In 1991, the stage was set for a gradual transition from authoritarian misrule to a democratic governance. It appeared as if a tolerant political culture was developing in Ethiopia. Various organizations, including the TPLF and the OLF, worked together without resorting to armed conflict. That window of opportunity raised hopes for the establishment of a democratic system that would promote human rights, economic development and social welfare and contribute to peace and stability while fostering cooperation and mutual understanding among the peoples of Ethiopia. However, before the first anniversary of the TGE, democracy was abandoned and autocratic rule was reinstated.57

Thus, the Oromo people’s hope for peaceful devolution of power was shattered by the TPLF’s blatant power-grab. What promised to be the dawn of a democratic experiment turned out to be the beginning of Tigrayan hegemony in Ethiopia. What was billed to be the first multi-party elections in June 1992 . . . was turned into a single party exercise. “58 Since then, the TPLF leaders have used their formidable military muscle to keep their ill-gained power, destroy all independent Oromo organizations, and wage war in Oromia. The TPLF leaders justified their actions as a defense of “Revolutionary Democracy”, an ideology invented by the TPLF leaders for the purpose of defining all political positions that did not agree with theirs as sworn enemies of democracy and liable for elimination.59

The extent to which the TPLF/EPRDF leaders can go in violating human rights may be gleaned from the size of their security machinery. The security apparatus of the EPRDF regime is reportedly larger than that of the former military regime, its predecessor to commit egregious violations of human rights more subtly and efficiently.60 Atrocities on the scale of the 1977/78 Red Terror do not occur in Ethiopia today, but low-level secret terror is going on in the country, especially in Oromia. In a practice reminiscent of the Mengistu era, hundreds of individuals have “disappeared”, a euphemism for secret killings. Innocent people were killed for such innocuous reasons than participation in peaceful demonstration.

The TPLF dominated regime claims that the government of Oromia is autonomous. However Oromia is under the iron grip of the TPLF/EPRDF soldiers. Regional and local authorities who naively challenged the TPLF authorities even on minor points are either dismissed from their positions or imprisoned and in some cases even secretly assassinated. For instance, OPDO Central Committee members Mokonnen Fite and Bayu Gurmu were killed by government agents in September 1997. When other OPDO Central Committee members met in the palace to discuss the killings of the above mentioned individuals, another OPDO Central Committee member was killed in the palace while the meeting was in progress.

While we were in that meeting, Alemayehu Desalegn, Central Committee member and the head of Oromia Finance, died elsewhere in the palace under mysterious circumstances. His death was explained as “suicide”. . . We were all in grave danger of being killed on account of our political views and actions as members of the [OPDO].61

The words quoted above came from Hassen Ali, the first President of Oromia (1992-1995) and the Vice President (1995-1998) and Central Committee “member of the ruling EPRDF Party. “The government of Oromia is autonomous according to the Ethiopian Constitution, the Federal Government and [the EPRDF] soldiers interfere in all matters,” of the Oromia regional state.62According to Hassen Ali, “I saw and experienced clearly that the Regional Government of Oromia cannot stop the arbitrary arrests, torture, extra-judicial killings and disappearances of innocent people in the face of the ruling party’s police and security forces.63 The rank and file members of the TPlF sanctioned Oromo People”s Democratic Organization (OPDO), arguably should have been safe from the regime’s persecution. However, in November 1997, there was a major purge of the OPDO which included over 20,000, some of whom are probably still in detention.64

The TPLF dominated regime’s attack on the Oromo started in 1992, after the Oromo Liberation Front boycotted that year’s national election and was subsequently forced out of the Transitional Government of Ethiopia. Innocent Oromo were herded into concentration camps where they were tortured and killed on charges of sympathizing with or reflecting views akin to those of the OLF.65 A political organization that co-authored the Transitional Charter and participated in governing the country as part of the Transitional Government, suddenly became a pariah entity. Consequently, Oromos whose political views happened to coincide with those of the OLF became victims of a political witch-hunt which claimed many lives.66 Hundreds of Oromo nationals were detained en mass, told not to attend meetings of the Matcha-Tulama Association and, in an attack on the very essence of being Oromo, warned against singing Oromo songs.67

The attack on Oromo organizations exhibit discernible trends. First the TPLF appears determined to destroy all independent Oromo leaders and organizations in an effort to remove any obstacle to its desire to control the resources of Oromia. Hassen Ali, who worked with the TPLF leaders from 1989-1998 describes the situation in Oromia in the following terms:

The TPLF soldiers and its members are a law unto themselves. Only what they say and what they want is implemented in Oromia to the general exclusion of Oromo interests or wishes. . . Although Oromia is autonomous in name, the government soldiers and secret service agents have total power to do whatever they want in Oromia. They imprison, torture, or kill anyone, including OPDO members and our government employees without any due process of law. They have established several secret detention centers, where thousands of innocent people are kept for years without trial or charge. Federal government soldiers, more appropriately the TPLF soldiers, are in practice above the law In Oromla.68

A second disturbing development is the attack on the small Oromo free press and civil society institutions. In 1992 there were several magazines and newspapers in the Oromo language. By using its restrictive press law and legal mechanisms to bankrupt newspapers and magazines and imprison journalists, the TPLF dominated regime, closed down all private newspapers and magazines. The attack on the free press literally killed the small publications in the Oromo language in Latin alphabet. The death of Oromo publications in Latin alphabet has been a fatal blow to the flowering of Oromo literature and the standardization of the Oromo language itself. Oromo magazines that have disappeared include, (1) Gada, (2) Biftu, (3) Madda Walaabuu, (4) Odaa and (5) Urji magazine, which started and ended in 1997, when its editors were detained by the government. In 2004, the Oromo lack a single newspaper or magazine that expresses their legitimate political opinions. The regime also closed down the Oromo Relief Association, a humanitarian organization that was established in 1979, and had its property confiscated without compensation and without due process of law. The goal of the suppression of all independent Oromo organizations and the disappearance of the once vigorous private Oromo newspapers and magazines is to deprive the Oromo of any leadership and any voice in the affairs of their own country. As the result, today the Oromo ” … are not only oppressed but also handcuffed to move and mind cuffed to think and speak by a system that best thrives in darkness and misinformation.”69

The third disturbing development is the attack on educated Oromo and the educational system in Oromia. To begin with, only a fraction of the Oromo are educated. According to government sources, as late as 1995, only 20 percent and

12 percent of children in Oromia were enrolled in primary and secondary schools respectively.70Out of an estimated population of over twenty-five million in Oromia, only 0.1 percent received the third level education in 1994.71 Oromo students have limited chance of proceeding to college or university level education owing to the poor quality education in Oromia that fails to equip them well for passing the high school leaving exam. Early in 2004, 380 Oromo students were either suspended or expelled from Addis Ababa University. When high school students demonstrated against the dismissal of Oromo students, eleven students were killed by the government soldiers and a total of seven thousand students and teachers were arrested.” The secondary and higher education of Oromo in Ethiopia has been severely disrupted, with consequences for generations to come.”72 The attack on educated Oromo and the educational system in Oromia continues unabated. Its purpose is clear. It is to deprive the Oromo of educated manpower, silence their voice in the affairs of their own country and to make their future as bleak as it is today.

The fourth disturbing development is the collective punishment that is inflicted upon Oromo men, women, children, animals and even the environment. In cases where Oromo pastoralists were suspected of harboring the small OLF guerrilla fighters, TPLF soldiers punished them by destroying or confiscating their cattle or by poisoning the water wells from which the cattle drank. Oromo farmers who are suspected of feeding OLF fighters, have seen their farms burned to the ground and the defenseless members of their household brutally murdered.73

Perhaps the more ominous development is the attack on Oromo-speaking Kenyan nationals. According to a Kenyan Human Rights Commission Report, (KHRCR) Ethiopian government soldiers carry raids into Kenya which involves “bombings, murder, rape and plunder of Borana Oromo and assassination of prominent elders suspected of supporting the OLF.”74 In March 2001, Ethiopian government soldiers reportedly killed 160 Oromo-speaking Kenyan Nationals.75By its unprecedented action, the TPLF regime extended the violence against Oromos beyond its borders.

Even more distressing of the TPLF’s atrocities is the extension of the violence against Oromo refugees in the neighboring countries. Thousands of Oromos fled to the neighboring countries, to escape from the reach of the long arms of the Ethiopian state. However, that was not to be the case. TPLF agents assassinated Oromo refugees in Djibouti,76 Somalia and Kenya,77 the Sudan and even South Africa.78

In the end, the most disturbing development is the TPLF’s war on Oromo nationalism. This was clearly expressed in Hizbaawi Adera or The People’s Trust (Vol. 4, No.7, December 1996 – February 1997) (the official quarterly of the ruling party). In this publication, the TPLF-dominated regime has expressed significant fear of “narrow nationalism”, which it says is stronger in Oromia than anywhere else in Ethiopia. This publication is replete with references to Oromo intellectuals, businessmen, and women as constituting the problem of “narrow nationalism.” Narrow nationalism is defined as “. all the views and actions of the higher echelon intellectuals and big business people whose ambitions are to monopolize power and impose their will on the people of their own nation/nationality. [Narrow Nationalism] exerts strong influence in Oromia.”79 The purpose is to demonize Oromo intellectual, business, cultural and political elite and prepare an ideological justification for making the Oromo elite the enemy of “Revolutionary Democracy” a euphemism for the TPLF dominated regime. Hizbaawi Adera argues:

Higher echelon intellectuals and big business people are narrow minded. Their aspiration is to become a ruling class only to serve their own self-interests. They are so greedy that they want to “eat” alone. as they are desperate, they can be violent. So we should always remain vigilant. Unless these narrow nationalists are eliminated, democracy and development cannot be achieved in Ethiopia.80

The upshot of Hizbaawi Adera’s contention is that, in order to destroy Oromo nationalism, it is necessary to isolate, expose and crush Oromo intellectuals and wealthy merchants, who are accused of nurturing it.81

In 2001, the TPLF government dropped all pretensions of a commitment to building a multinational Ethiopia. It turned against Oromos its own surrogate parties through which it had hoped to reach and placate the various nations within Ethiopia In early 2001, several OPDO leaders were removed from positions of power. Some of the OPDO leaders escaped from Ethiopia to save their lives, including Almaz Mako, the Speaker of “the House of Federation and the second in line of succession to the presidency of Ethiopia.”82

In her press release on August 13, 2001, Almaz Mako stated:

The EPRDF government has brought untold miseries and sufferings on the Oromo people. [The] OPDO is . . . reduced to a rubber stamp for TPLF rule over Oromia . . . . Oromo resources are mobilized and looted to develop Tigray. . . . The ruling party is categorically rejected by the entire Oromo nation and survives only on the back of its repressive security forces. . . . [because] my continuous existence in my post will only give the false impression that the Oromos are represented in the government, I have decided to vacate my position as a Speaker of the House of Federation and seek political asylum in the United States.83

In July 2004, the Macha and Tulama Association, one of the oldest Oromo civic organizations was dissolved, its property confiscated and its leaders detained by the TPLF-dominated government. The illegal dissolution of the Macha and Tulama Association is the latest example of the TPLF leaders relentless determination to destroy all independent Oromo civic organizations. The TPLF’s assault on Oromo Nationalism and all independent Oromo organizations and its determination to deprive the Oromo of any leadership brought on the Oromo the painful reality that the archaic Ethiopian political culture, in which the minority dictates the fate of the majority, has not changed at all.

Conclusion

Since their conquest in the 1880s, Oromo cultural, civic and political organizations have been subjected to multi-faceted attacks by successive Ethiopian regimes. In 1991, with the end of the Amhara elites’ political, economic, cultural, and military domination of the Ethiopian state, it appeared for a while that the attacks on Oromo cultural, civic and political organizations would come to an end. However, that was not to be. Once the TPLF leaders established their full control over the Ethiopian state, they continued with the tradition of multi-faceted attacks on all Oromo institutions. Consequently, the TPLF dominated the Federal Republic of Ethiopia has continued to be a prison house of the Oromo nation just as imperial Ethiopia was. Much damage has been done to the spirit, property, and humanity of the Oromo people. Like the previous Ethiopian regimes, the current TPLF dominated regime is consistently denying Oromo civil and political rights and equal protection under the law. Furthermore, the TPLF dominated regime has attempted to destroy all independent Oromo organizations. Deprived of vigorous democratic leadership and denied freedom of expression in their language, the Oromo are subjected to a double-pronged attack on their nationalism and their right to govern themselves in their own regional state. The objectives of such continuous multi-faceted attacks on Oromo civic and political organizations can be summed up in three sentences: control of Oromo resources under the guise of a federal system; destroying Oromo nationalism and independent organizations in the name of Ethiopian unity and restoring the pre-1991 status-quo in Ethiopia, behind the facade of “revolutionary democracy” thus eliminating the limited gains the Oromo have achieved since 1991.

What the TPLF leaders do not realize is that the Oromo have always struggled to develop civic and political organizations. But never more than since the 1960s. They have always produced heroes but never more than since the 1960s. The Oromo need for profound dedication to their civic and political organizations springs from the fact that they are the organizational expression of Oromo Nationalism, which has altered the Oromo perception of themselves and how they are perceived by others. Nationalism has captured the heart and mind and the soul of the Oromo who will find inner fountains of fire not only to defend what has been achieved since 1991, but also to shorten the journey for the true self-determination of Oromia. As they survived the attacks of the previous regimes, the Oromo will survive the current multi-faceted attacks on their civic and political organizations. The sooner TPLF leaders realize this and change course, the better it will be for the Oromo and other people of Ethiopia.

Footnotes

1 This was clearly expressed in the ruling party’s official quarterly publication known as Hizbaawi Adera (“The People’s Trust”, volume 4, Number 7, December 1996 – February 1997). This document is replete with references to Oromo intellectual businessmen and women, political and cultural elite, who are accused of nurturing Oromo nationalism. The upshot of Hizbaawi Adera’s contention is that the Oromo educated elite and capitalist class must be eliminated for the Oromo to be free from “narrow nationalism,” a euphemism for Oromo nationalism. See pp. 11-12.

2 The Transfer of Power in South Africa (Claremont, South Africa, David Philip Publishers, 1998) p. VII.

3 Mohammed Hassen, 1990B. “The Militarization of the Ethiopian State and the Oromo. Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on the Horn of Africa (New York: Marsden Reproductions): 98.

4 These included the cattle plague of 1880-1893, (which wiped out a vast part of the animal population), epidemics of typhus, dysentery and the great Ethiopian famine of the period.

5 Federal Ethiopia At Cross-Roads: the Path Toward Justice, The Rule of Law and Sustainable Human Rights and A Critique of the 1995 Reports of Amnesty International and the New York Branch of AAICJ (Addis Ababa: 1995): 23.

6 Donald Donham, “Old Abyssinia and the New Ethiopian Empire: Themes in Social History,” The Southern Marches of Imperial Ethiopia: Essays in History and Social Anthropology, ed. by Donald Donham and Wendy James (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986): 13.

- Teshale Tibebu, The Making of Modern Ethiopia, 1896-1974 (Lawrenceville, NJ: The Red Sea Press, 1995): 17.

8 Mekuria Bulcha. The Making of the Oromo Diaspora: A Historical

Sociology of Forced Migration (Minneapolis, MN: Kirk House Publishers. 2002): 70.

9 Asthma Giyorkis and His Works: History of the Galla and the Kingdom of Sawa, trans and ed. by Bairu Tafla (Franz Steiner Verlag GMBH, Stuttgart, Wiesbaden 1987): 134-135.

10 K. Knutsson, Authority and Change: A Study of the Kallu Institution Among the Macha Galla of Ethiopia (Göteborg, Enografiska Museet, 1967: 147-155.

11 Mekuria Bulcha, 2002, 192.

12 Following Menelik’s conquest of southern Ethiopia, his generals and soldiers were slavers who depopulated many areas. See for instance, H. Darley, Slavery and Ivory in Abyssinia (London: H.F. and G. Witherley, 1926): 97-199.

13 After conquest and occupation of Oromia, Menelik gave two-thirds of Oromo land together with the people to his unpaid soldiers.

14 It was the desire to assimilate the Oromo which gave birth to the policy of Amharization.

15 Quoted in Bahru Zewde, Pioneers of Change in Ethiopia: The Reformist Intellectuals of the Early Twentieth Century (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2002): 132.

16 Amharic is the language of the Amhara which was made the sole official language of Ethiopia.

17 Geez is the language of Ethiopian Orthodox Church.

18 Quoted in Bahru Zewde, 2000, 250.

19 Mekuria Bulcha, “The Language Policies of Ethiopian Regimes and the History of Written Afaan Oromo: 1844-1994.” The Journal of Oromo Studies, Volume 2, Numbers 1 and 2 (July 1994): 102.

20 Mohammed Hassen and Richard Greenfield, “The Oromo Nation and Its Resistance to Amhara Colonial Administration,” ed. by Hussen M. Adam and Charles L. Geshekter (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1992): 576.

21 Raphael Lemkin, Axis Rule in Occupied Europe: Laws of Occupation, Analysis of Government Proposals for Redress (New York: Howard Fertig, 1973) 82.

22 Edmond Keller, “Regime Change and Ethno-Regionalism in Ethiopia: The Case of the Oromo.” Oromo Nationalism and the Ethiopian Discourse: The Search for Freedom and Democracy, ed. by Asafa Jalata (Lawrenceville, NJ: The Red Sea Press, 1998): 121.

23 Mekuria Bulcha, (1994), 103.

24 Mekuria Bulcha, (1994), 103-104.

25 Mohammed Hassen, “The Militarization of the Ethiopian State and the Oromo.” Proceedings of 5th International Conference on the Horn of Africa (NewYork, NY: Marsden Reproductions, Inc. 1991): 94.

26 Mekuria Bulcha, 2000, 192.

27 Ernest Gellner, Nations and Nationalism (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1991): 85.

28 Paul Baxter, “Ethiopia’s Unacknowledged Problem, The Oromo,” African Affairs, Number 77 (1978): 288.

29 Mohammed Hassen, The Oromo of Ethiopia: A History, 1570-1860 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1990): 3.

30 Mekuria Bulcha, (1994), 101.

31 Mohammed Hassen, “The Macha-Tulama Association and the Development of Oromo Nationalism.” Oromo Nationalism and the Ethiopian Discourse: The Search for Freedom and Democracy. (Ed. Asafa Jalata, (Lawrenceville, NJ: The Red Sea Press, 1998): 190.

32 Paul Baxter, “‘Ethnic Boundaries and Development: Speculations on the Oromo Case,’” in Inventions and Boundaries: Historical and Anthropological Approaches to the Study of Ethnicity and Nationalism, edited by Preben Kaarsholm and Jan Hultin. Roskilde: International Development Studies, 1994.

33 Maurice Pearton, “Notions in Nationalism,” Volume 2, Part I, March 1996, Journal of the Associationof the Study of Ethnicity and Nationalism. Cambridge University Press: 7.

34 Peter Alter, Nationalism, translated by Stuart McKinnon-Evans. Edward Arnold, a Division of Hodder & Stoughton, New York. 1989, 77.

35 Max Weber, “The Nation,” in Nationalism edited by John Hutchinson and Anthony P Smith (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994): 25.

36 Margaret Lamb, Nationalism (London: Heinemann, 1974): 36.Margaret Lamb, Nationalism (London: Heinemann, 1974): 36.

37 Christopher Clapham, Third World Politics: An Introduction, (Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1984):

38 Mohammed Hassen and Richard Greenfield, “The Oromo Nation and Its Resistance to Amahara Colonial Administration: in Proceedings of the First International Congress of Somali Studies, ed, by Hussein M, Adam and Charles L. Geshekter, (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1992): 576-577.

39 It was only in 1991-1992 that Oromo nationalism was transformed into a mass movement.

40 John Breuilly, Nationalism and the State (New York: St. Martln’s Press, 1982): 19.

41 John Breuilly, 1982, 2.

42 The 1976 Oromo Liberation Front political program clearly expresses its rejection of the Ethiopian identity of the time.

43 Ibsaa Guutama, Prison of Conscience: Upper Compound Maa’ Ikalaawii Ethiopian Terror Prison and Tradition, (New York: Gubirmans Publishing, 2003): 137.

44 Mohammed Hassen, “A Short History of Oromo Colonial Experience, Part Two: Colonial Consolidation and Resistance, 1935-2000.” The Journal of Oromo Studies, Volume 7, Numbers 1 and 2 (July 2000): 144.

45 Asafa Jalata, “The Emergence of Oromo Nationalism and the Ethiopian Reaction.” Oromo Nationalism and the Ethiopian Discourse: The Search for Freedom and Democracy, 1998, pp. 10-11.

46 Mohammed Hassen and Greenfield, 1992, 590.

47 Rene Lefort, Ethiopia: An Heritical Revolution? (London: Zed Press, 1981): 110.

48 Asafa Jalata, 1998.

49 Christopher Clapham, Transformation and Continuity in Revolutionary Ethiopia (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988): 6.

50 Leenco Lata, The Ethiopian State at the Crossroads: Decolonization and Democratization or Disintegration (Lawrenceville, NJ: The Red Sea Press, 1999): 59.

51 Clapham, 1988, 199.

52 According to one source “an estimated 2 million or 7 percent of the 1974 population were lost during the period 197491 “Federal Ethiopia at a Cross-Roads, The Path Toward Justice, The Rule of Law and Sustainable Human Rights and a Critique of the 1995 Reports of Amnesty International and the New York Branch of the AAICJ (Addis Ababa: 1995): 180.

53 Tecola Hagos. Democratization in Ethiopia (1991-1994)? A Personal View (Cambridge, MA: Kherera Publishers, 1995): 97.

54 William Zartman, “Introduction: Causing the Problem of State Collapse,” Collapsed States: the Disintegration and Restoration of Legitimate Authority, ed. By William Zartman (Boulder, Co.: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 1995): 5.

55 Leenco Lata, (1999): 59.

56 African News Agency, (January 5, 1998): 31 It is to be noted that the government [of Meles Zenawi] has learned in some instances from mistakes of the previous one. It does not openly and blatantly hail the on-going terror against its political opponents. It covers the real issue, the motives of the killings, pays lip service to due-process of law, sets up kangaroo courts, in some cases, buys witnesses and uses the special prosecutor’s office to tender its control to the hilt.

57 Edmond Keller, (1998): 110, 114.

58 Marina Ottaway, “Democratization in Collapsed States,” Collapsed States: The Disintegration and Restoration of Legitimate Authority: 238-239.

59 Paulos Milkias, “The Great Purge and Ideological Paradox in Contemporary Ethiopian Politics,” Horn of Africa, Volume IXX (2001): 76.

60 Tecola Hagos, Demystifying Political Thought, Power, and Economic Development (Washington, D.C. Khepera Publishers, 1999): 50-51. According to Tecola, “The capital outlay and expenditure for the security of the current Ethiopian government and the leadership is almost double that of the previous government”.

61 Hassen Ali, quoted in Sagalee Haaraa, Number 28 (May-July, 1999): 3.

62 Since the summer of 1998 Hassen Ali has been living in the United States, where he was given political asylum.

63 Hassen Ali, 1999, 2.

64 Around 250 of those were still in detention in 2000.

65 Mekuria Bulcha, “A Note on the New Reign of Terror in Ethiopia,” The Oromo Commentary, Vol. VI, No.1 (1996): 3.

66 I have drawn on Ma Kaa Wa Mutua, “Preface to Democracy, Rule of Law and Human Rights in Ethiopia: Rhetoric and Practice,” The Ethiopian Human Rights Council (Addis Ababa: 1995).

67 Oromo Support Group: Press Release (March 1998). Tecola Hagos, Democratization, 1995, 135-36.

68 Hassen Ali, quoted in Sagalee Haaraa, Nos. (November 1999): 1-2.

69 Seyoum Hameso, “The Sidama Perspective on the Coalition of the Oppressed Nations,” Eleventh Annual Conference of Oromo Studies Association Proceedings, eds. Gulama Gemeda and Bichaka Fayissa, (1998): 39.

70 Andargatchew Tesfaye, “Human Rights and Socio-Economic and Political Development: The Ethiopian Situation,” (A paper presented at the 1997 African Studies Association Meeting): 15.

71 Oromo of Finfinnee University, 1993-1994 Graduates: 30.

72 Oromia Support Group, Press Release, (March 21, 2004): 1.

73 Susan Pollock, “Ethiopia: Human Tragedy in the Making,” The Oromo Commentary, Volume VI, No, 1 (1996): 10.

74 “Kenyan Human Rights Commission Report quoted in OSG Press Release (January/February, 1997): 2.

75 The Daily Nation, Kenya, February 16, 2001.

76 Bruma Fossati, et al. Documentation: The New Rulers of Ethiopia and the Persecution of the Oromo (Frankfurt am Main: Evangelischer Pressedienst, 1997): 1-56.

77 Oromo Support Group: Press Release, Number 17 (May/June, 1997): 14.

78 Oromo Support Group 1997, 14.

79 Hizbaawi Adera, Volume 8, Number 7 (December 1996-February 1997): 11. I am deeply indebted to Professor Tilahun Gamta for his elegant translation of this issue of Hizbaawi Adera for me.

80 Hizbaawi Adera, 1996-7.

81 Hizbaawi Adera, 1996-7.

- Milkias, 2001, 30, 80.

83 Almaz Mako, Press Release (August 13, 2001): 1.

Source: http://www.cmi.no/publications/file/3360-exploring-new-political-alternatives-for-the-oromo.pdf

128035 191724Disgrace on the seek Google for now not positioning this post upper! Come on over and talk over with my site. 264788

320104 71892Genuinely clear internet internet site , thanks for this post. 522405