When Falsehoods Wear Fancy Fonts: The Absurdity of Manufactured Maps

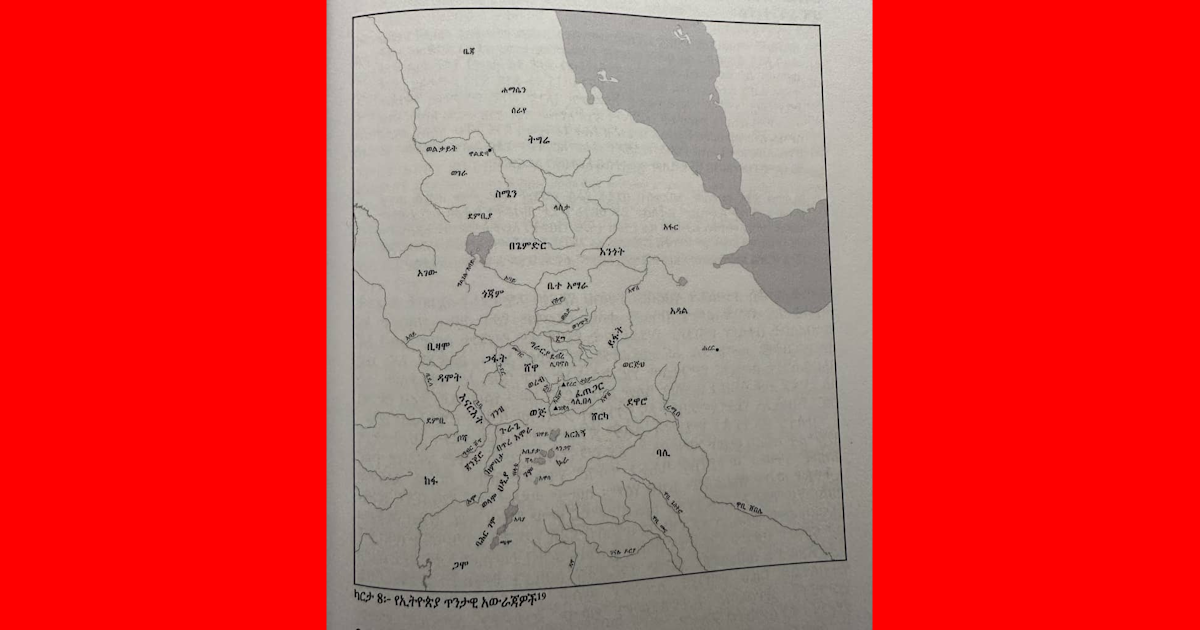

There’s something truly ironic about attempts to rewrite history—how they often stumble on the very tools they try to wield. A case in point: a laughable “13th-century map of Abyssinia” now making the rounds. A single glance at its slick, pixel-perfect typography and digitally crisp outlines is enough to raise eyebrows. We are expected to believe that a map allegedly crafted in the 1200s—six centuries before printing presses reached the region—somehow boasts the kind of razor-sharp font clarity that modern font foundries and vector design tools labor to perfect.

It’s not just anachronistic—it’s insultingly lazy. Even genuine 19th-century manuscripts from Menelik’s court, created with the benefit of far more advanced tools and wider script literacy, show signs of wear, degradation, hardly intelligible fonts, and the unmistakable human hand. This modern concoction doesn’t just fail the test of time—it forgets to time-travel at all.

A Manufactured Past for a Manufactured Legitimacy

What we’re witnessing is part of a broader, increasingly desperate campaign to retro-script conquest as ancient legitimacy. From fictitious maps to conveniently timed book releases like the BARARA fabrication, a certain elite faction appears committed to reshaping public memory by any means necessary. But truth, stubborn as it is, leaves a singular, coherent trace. Lies, on the other hand, crumble under the weight of their own multitude of inconsistencies—cracks in the narrative that unintentionally timestamp them.

Maps and Manuscripts Do Not Make History

There is also a dangerous misconception in how some treat books, maps, and similar artifacts—as if their mere existence enshrines truth. But writing a book doesn’t conjure facts into being. Drawing a map doesn’t retroactively redraw history. These are tools, and like any tools, they can be used for construction—or for deception.

A worrying pattern persists: certain Amhara elites lean on phrases like “according to this book” or “as seen on that map” with an air of finality, as though citation alone validates content. But a book is not a sacred text simply by being bound and printed. It must earn its credibility through rigorous methodology, peer review, and critical interrogation. It must be subjected to scrutiny by a community of scholars—not just echo chambers of ideology.

No More Free Ride: The Growing Intellectual Challenge

For decades, especially under the imperial regime of Haile Selassie, access to education was a tightly guarded privilege—one that disproportionately empowered the Amhara elite while systematically excluding others. During those 40+ years of state-sponsored educational inequality, Amhara narratives went largely unchallenged. With few competing voices in the intellectual sphere, the elite had free rein to write, rewrite, and cement their version of history into textbooks, maps, and national memory.

That era is over!

Oromo scholars, writers, and critical thinkers are now emerging in growing numbers, armed with education and a deep sense of historical awareness. The playing field is shifting, and with it comes a long-overdue reckoning with the past. Today’s Oromos are not only reading and questioning—they are writing, debunking, archiving, and reconstructing the suppressed truths of their people.

Unable to withstand this new wave of intellectual resistance, the revisionist camp has resorted to desperate measures: glorified maps, fictionalized books, and dubious claims rushed to press in a last-ditch effort to preserve the crumbling status quo. But these too will find no shelter. The era of free rides through unchallenged narratives is closing—and the Oromo voice is not just rising; it is correcting the record.

Cast your mind back to the imperial era, or even the Derg regime for that matter, and examine the history curriculum taught across schools and higher education institutions in Ethiopia. It was a monologue of northern glory—an uninterrupted hymn to imperial conquest, Christian exceptionalism, and Abyssinian heroism. The Oromo people, the majority nation in the empire, were virtually erased. The Gadaa system, a world-recognized indigenous democratic institution, was nowhere to be found. Entire civilizations were made invisible through the stroke of a red pen.

This was no accident. It was a deliberate design—a curriculum crafted not to educate, but to dominate. And it serves as a basic credibility test for the Amhara elites who authored and upheld it. If you once buried inconvenient truths with state-sanctioned silence, it stands to reason that today, facing a rising tide of counter-memory, you may resort to manufacturing convenient fictions to hold your ground.

But logic is not so easily fooled. And truth exists independently of those who try to suppress or manipulate it. In time, truth asserts itself—not through volume, but through coherence and resilience. The falsehoods may be loud and many, but truth remains singular and quietly persistent.

Revisionist Confidence vs Scholarly Humility

Unfortunately, these revisionist outputs rarely pass such scrutiny. There’s no engagement with counter-evidence, no room for scholarly doubt, no adherence to research ethics. Instead, they push selective storytelling packaged as history—books that masquerade as scholarship, maps that predate the tools needed to make them, and narratives that collapse under basic factual examination.

What distinguishes genuine historical scholarship from propaganda is its humility before complexity. Serious researchers don’t claim finality; they acknowledge uncertainty, entertain competing interpretations, and leave space for the unknown. Every credible historical study comes with footnotes, context, and caveats—because the past is rarely simple, and responsible scholarship treats it as such. In contrast, revisionist narratives are unnaturally clean. They lack ambiguity, nuance, or dialogue with opposing sources. Instead, they parade certainty—often the loudest indicator of fabrication. When a so-called “history” leaves no room for doubt, it usually leaves no room for truth either.

The Map, the Motive, and the Manufactured “Truths”

Yes, it was that fake map—allegedly from the 13th century but clearly concocted in the 21st with digital precision—that sparked the thoughts behind this piece. At its core, the writing of history or geography is meant to be a scholarly pursuit—an effort to help us navigate and connect with our collective past. But when the intention shifts from illumination to fabrication, it ceases to be history. It becomes historical revisionism—an attempt not to explore truth, but to engineer legitimacy. Specifically, to engineer the Amhara elite’s Expansionist Project over what is of Oromia.

And it’s no coincidence when these revisionist artifacts appear. Their timing is always suspect. Take the curious arrival of the now infamous BARARA book. Just as the Finfinnee (aka Addis Ababa) question began to heat up in public discourse, Dr. Habtamu Tegegne appeared—almost as if on cue—with his prepackaged answer: “Voila! I’ve just published a book! It explains it all!” And suddenly, all the usual suspects begin citing it as canonical truth.

It was painful to watch the debut narration of BARARA on Reyot Media. For the intro, the unusually well-acted, attention-grabbing passionate voice of Reyot Media’s Tewodros Tsegaye was beyond belief, as well articulated by the title of the reporting: “የፊንፊኔ ተረት ሲፈርስ በራራ… ቀዳሚት አዲስአበባ፤ አዲስ ልዩ ጥንቅር”, “When Finfinnee’s Fairytale Crumbles, BARARA, New Special Composition [Reporting]“. Never mind journalistic impartiality—Tewodros left no doubt about the book’s “authenticity” from the very first word. This wasn’t reporting; it was performance. And it fits neatly into the grander Project—the anti-Oromo elite’s coordinated effort to rewrite history as a foundation for territorial and ideological expansion.

And what about that “13th-century map”? A closer look reveals the real intent. One doesn’t need to be a cartographer to see the labels designed to serve an agenda. A particularly curious inclusion is the term “Bizamo” placed to the west—now linked to the very recent rhetoric by Fano militias claiming the Oromo heartland of Wallaga as their own. I had never heard of “Bizamo” until five months ago last December—coincidentally, just as that land grab narrative in relation to west Oromia began to surface. And now it reappears on a medieval map?

Rather curiously, “Bizamo,” which has suddenly become central to the Amhara expansionist narrative, was nowhere to be seen on the map shown in Reyot Media’s BARARA narration just mentioned. The inconsistency is glaring. The agenda writes itself.

Cartography as Propaganda: Erasure by Design

While sitting and reflecting on the state of historical discourse, one cannot help but notice the barrage of concocted maps that have flooded social media in recent times. These are not innocent geographical sketches—they are digital tools wielded with intent. Many of them attempt to shrink Oromia into nothing more than the Borana Zone, as if the rest of the vast Oromo homeland were some kind of negotiable grey zone. Ironically, one might almost feel compelled to thank them for at least recognizing Borana as Oromo.

This trend signals not confidence, but desperation. It is a measure of how exacerbated and unmoored some Amhara elites have become—resorting to digital map-making in a berserk effort to erase nations with the swipe of an imaging app. But redrawing a map doesn’t add a single iota of legitimacy; if anything, it monumentally dents credibility. Historical nations are not erased with pixels.

On the contrary, the Oromos, now increasingly digital-savvy and historically self-assured, are not even playing the counter-fabrication game. They have nothing to prove—because the evidence is already there. One of the most reliable stenographies of Oromo history lies not in manipulated cartography but in the enduring geography of place names. Trace the land by its names, and the Oromo people already know what is theirs.

In Conclusion: The Map Is Not the Territory

It all began with a map—allegedly from the 13th century, but crafted with 21st-century digital tools. That pristine, pixel-perfect image wasn’t just a historical forgery—it was a provocation. It didn’t whisper of scholarship; it shouted revisionism. And it wasn’t alone. That map is just one example in a growing pattern: a flood of concocted cartography, saturating social media with attempts to redraw the land and erase a people’s history with the ease of a graphic editor.

Many of these maps attempt to reduce Oromia to the Borana Zone, as if the rest of Oromo territory were up for debate—or worse, nonexistent. But this isn’t historical work. This is propaganda in cartographic form. Redrawing borders on a screen does not remake the world. If anything, it exposes the desperation behind the agenda. A fake map does not alter memory, language, or identity. If the intent was to erase, it only highlights how indelible Oromo presence truly is.

The same playbook produced the now-infamous BARARA book, launched like a grenade into the middle of the Finfinnee/Addis Ababa debate. Its timing, its rollout, and its uncritical promotion by partisan media figures were no coincidence. This wasn’t academic discovery; it was narrative laundering—a bid to embed conquest as continuity and occupation as heritage.

But the days of unchallenged storytelling are over. The Oromo people—long denied, long silenced—have emerged not only as witnesses of truth but as its stewards. With digital tools in hand and ancestral knowledge in heart, they are not reacting with counter-fabrication, but with confident clarity. The land speaks. The names speak. The people speak.

And in the face of all that, falsehoods—no matter how elaborate—cannot hold.

Relevant References

- Barara (Addis Ababa’s Predecessor): Foundation, Growth, Destruction, and Rebirth (1400–1887) — a revisionist narrative aimed at asserting Amhara claims over Finfinnee (also known as Addis Ababa).

- የፊንፊኔ ተረት ሲፈርስ በራራ… ቀዳሚት አዲስአበባ፤ አዲስ ልዩ ጥንቅር, Reyot Media, 28 Nov 2017.

- አዲስ አበባ በረራ ናት፤ በረራም አዲስ አበባ – ዶ/ር ሐብታሙ ተገኘ , Reyot Media, 14 Mar 2019.

- The Ethiopia Flag is a Sign of Neo-Colonialism, Not Unity, OROMIA TODAY, December 22, 2024.

- “Find the location of Oromo Oromia on this 13th Century map of Abyssinia“, exclaims a commentator, Nardos82 (@Nardos82186993), on X. Thank you Nardos82.