Introduction

The Oromo struggle for self-determination is once again at a critical crossroads. As anger intensifies toward Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s authoritarian consolidation of power, many Oromo activists have increasingly defined the movement’s primary objective as bringing down Abiy. While such opposition is justified by state brutality and betrayal of earlier promises, defining our national struggle in terms of removing a single figure risk repeating historical errors — errors we have made, tragically, in 1974, 1991, and 2018.

This paper contends that:

- Personalizing the Oromo question around Abiy is strategically flawed.

- Historical experiences show regime change without structural transformation is self-defeating.

- We must act with vision and discipline, regardless of whether Abiy falls soon or remains in power for a little while.

A. The Problem With Centering Abiy in Oromo Political Strategy

A.1. Personifying a Structural Problem

The Ethiopian state is a centralized imperial construct that long predates Abiy Ahmed. Its mechanisms of marginalization — including settler colonial land practices, linguistic domination, and political exclusion — were established in the 19th century under Emperor Menelik II and perpetuated through subsequent regimes. Abiy’s emergence is a continuation of this historical trajectory, not a rupture from it [1].

Defining liberation by a leader’s removal risks confusing symptoms for root causes. The empire’s survival has never depended on a single ruler but on deeply embedded structures that persist through coups and transitions.

A.2. Tactical Mobilization Without Strategic Clarity

When the enemy is a person, mobilization can be immediate but shallow. While slogans like “Down with Abiy!” energize the street, they do not answer essential political questions: What comes next? Who leads the transition? What guarantees Oromo autonomy? Without strategic clarity, movements fall into reactionary patterns, easily hijacked by rival elites with deeper state access.

B. What We Learned From 1974, 1991, and 2018

B.1. The Derg and the Eclipse of Grassroots Revolt (1974)

Oromo nationalists and student activists joined hands with Amhara, Tigrayan, and Eritrean revolutionaries to topple the monarchy. Yet once the Derg seized power, Oromo national identity was violently suppressed. The Macha-Tulama Association was banned; its leaders imprisoned or executed [2]. The revolution gave birth to military centralism, not liberation.

B.2. TPLF Ascendancy and the Failure of Genuine Federalism (1991)

Oromo nationalists, through the OLF, briefly participated in the transitional government. However, the Tigrayan-led TPLF maneuvered to marginalize the OLF and monopolized state institutions [3]. The 1995 constitution promised federalism, but its implementation was selective and hollow. Oromia existed as a unit on paper but lacked sovereignty in governance, security, and development.

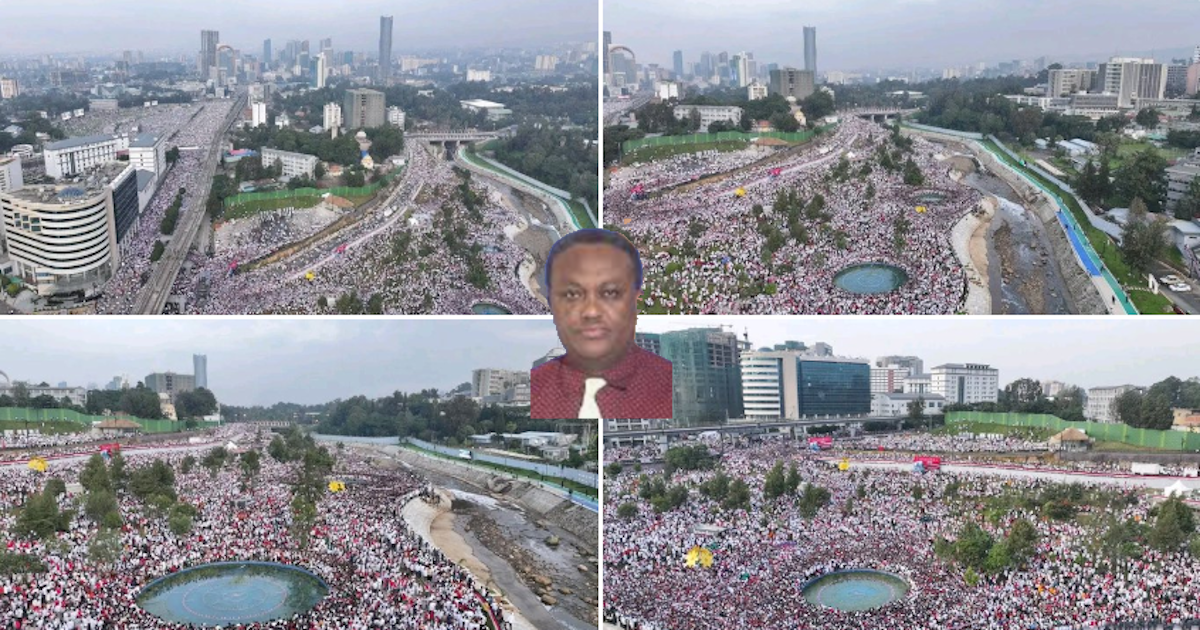

B.3. Abiy’s Rise and the Subversion of Qeerroo Gains (2018)

The Qeerroo-led youth protests destabilized the TPLF regime and created the conditions for political opening. However, Abiy Ahmed co-opted Oromo grievances to facilitate his rise to power, only to betray them once in office: by systematically destroying the Qeerroo leaders, vilifying Oromo self-assertion, outlawing opposition parties, militarizing Oromia, unleashing a devastating paramilitary and military rule through endless state of emergency, and promoting a neo-unitarist narrative [4,5].

[^4]: Human Rights Watch, “Ethiopia: No Justice in Crackdown on Oromo Protest,” October 2019.

[^5]: Amnesty International, “Beyond Law Enforcement: Human Rights Violations by Ethiopian Security Forces in Oromia,” May 2020.

C. What Must Be Avoided

C.1. Mistaking Regime Change for Liberation

As in 1991 and 2018, many Oromo believed that removing an oppressive regime would lead to self-rule. Yet structural power remained in the hands of Habesha-dominated elites. Without a defined roadmap and negotiating leverage, new regimes inherit old institutions.

C.2. Entering Transitional Periods Without Guarantees

Both the 1991 and 2018 transitions excluded Oromo actors from meaningful power. The OLF, in 1991, was expelled after token inclusion; in 2018, Oromo opposition groups were welcomed as symbols, then outlawed or suppressed. No written promises or transitional pacts protected Oromo interests. The Oromo were not in a position to force change through military means. Now, we are building OLF-OLA, shouldn’t we think differently?

C.3. Dividing Over Tactics and Personalities

Factionalism, particularly within the OLF and the wider nationalist camp, has weakened Oromo unity. Disputes over whether to use armed or peaceful means, and rivalries over legitimacy, have repeatedly invited state manipulation. The only viable alternative is strengthening OLF-OLA. The old guard must pass the button to the next generation.

D. What We Must Do — Whether Abiy Falls or Not

D.1. Reaffirm the Core Goal: Oromo Self-Determination

The original aim — articulated since the 1970s by the OLF — is the right of the Oromo nation to self-determination.[^6] Whether that takes the form of sovereign statehood or confederal autonomy, the right must be exercised through the democratic will of the Oromo people.

[^6]: Oromo Liberation Front (OLF), “Political Program of the OLF,” (Original 1976).

D.2. Build and Protect Oromo Institutions

Resilient movements require:

•An accountable OLF-OLA or successor body with unity of purpose.

•A strategic OLF-OLA with political education and command control.

•Independent media, civil society, and diaspora advocacy that coordinates effectively.

D.3. Prepare a Post-Abiy Framework Now

Avoid the 1991 and 2018 traps. Prepare:

•A transitional justice demand: for massacres in Oromia, political detentions, and land theft.

•A negotiation blueprint: conditions for any federal reconstitution or exit.

•A red line doctrine: minimum acceptable terms before entering any transitional pact.

D.4. Build Strategic, Not Opportunistic, Alliances and Work On Designed Removal of Abiy

Partnerships must be based on mutual recognition of nations’ rights. Oromo alliances with Sidama, Somali, Tigray, and Southern nations can be built on federal restructuring or right to self-rule. However, alliances with Habesha unitarists or “Ethiopianist” opposition must be treated with caution unless they stop name calling and vilification followed by publicly endorse Oromo autonomy.

Conclusion: History Is Trying to Teach Us

Abiy Ahmed may fall — and I believe he must. He shouldn’t have been allowed to be there in the first place. But if the Oromo struggle remains reactive, centered on individuals, and lacking strategic depth, his fall will become another missed opportunity.

The empire does not collapse when its rulers do; it reshapes itself in the absence of organized alternatives. The Oromo must therefore not just fight injustice, but define the terms of justice in advance.

“Those who do not learn from history are doomed to repeat it. But those who learn it too late are doomed to repeat it faster.”

Let us not be late again.

References

- Asafa Jalata, Oromo Nationalism and the Ethiopian Discourse: The Search for Freedom and Democracy (Lanham: University Press of America, 1996), pp. 45–68.

- Mohammed Hassen, The Oromo and the Christian Kingdom of Ethiopia: 1300–1700 (James Currey, 2015), pp. xiii–xvi; also see Amnesty International, “Ethiopia: Political Detainees and Prisoners of Conscience,” AI Index: AFR 25/001/1986.

- Leenco Lata, The Ethiopian State at the Crossroads: Decolonization and Democratization or Disintegration? (Lawrenceville, NJ: Red Sea Press, 1999), pp. 151–176.

- Human Rights Watch, “Ethiopia: No Justice in Crackdown on Oromo Protest,” October 2019.

- 4.Amnesty International. “Beyond Law Enforcement: Human Rights Violations by Ethiopian Security Forces in Oromia.” May 2020.

5.Human Rights Watch. “Ethiopia: No Justice in Crackdown on Oromo Protest.” October 2019.

6.Oromo Liberation Front. “Political Program of the OLF,” Published 1976.

7.Amnesty International. “Ethiopia: Political Detainees and Prisoners of Conscience,” AI Index: AFR 25/001/1986.